Listen to the article

Soviet underground artist Erik Bulatov, who transformed Communist propaganda into poignant art, dies at 92

Erik Bulatov, a pioneering artist whose bold works became emblematic of Soviet underground art by juxtaposing Communist propaganda against idyllic landscapes, passed away last month at the age of 92.

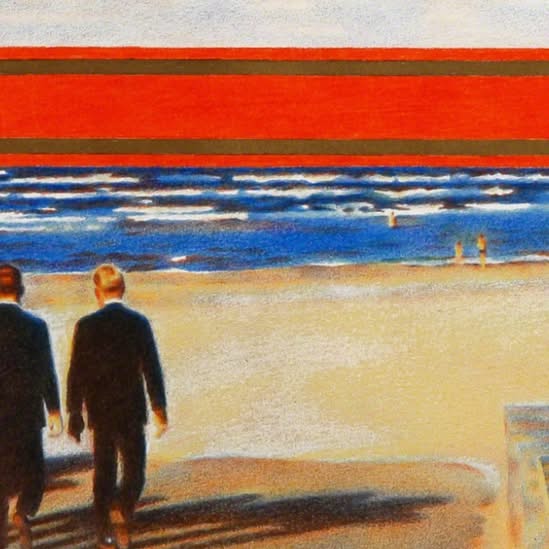

Throughout his career spanning more than six decades, Bulatov developed a distinctive visual language that critically examined the relationship between political power and everyday reality in Soviet society. His most recognized works featured stark Communist Party slogans painted across tranquil blue skies, peaceful beaches, and serene natural settings – a visual metaphor for the intrusion of state ideology into citizens’ lives.

Born in 1933 in Sverdlovsk (now Yekaterinburg), Bulatov came of age during Stalin’s reign, graduating from the Surikov Art Institute in Moscow in 1958. While officially working as a children’s book illustrator to earn a living, he developed his true artistic vision outside the sanctioned Soviet art establishment.

“I was interested in the border between reality and the social space occupied by Soviet ideology,” Bulatov once explained in a 2017 interview. “My paintings attempt to show how these slogans and symbols invaded our consciousness and transformed our perception of the world around us.”

Bulatov’s most famous works include “Krasikov Street,” featuring the phrase “Glory to the CPSU” (Communist Party of the Soviet Union) emblazoned across a blue sky, and “Soviet Cosmos,” where red Soviet text overwhelms a natural landscape. These pieces represented a quiet but powerful resistance against the regime’s totalitarian control over public expression.

Unlike some contemporaries who embraced more abstract forms of dissent, Bulatov maintained a realistic painting style while incorporating text and Soviet imagery as his form of subversion. This approach positioned him as a key figure in the Sots Art movement, the Soviet equivalent to Western pop art that appropriated and recontextualized official propaganda.

“Bulatov understood that the most effective critique of the system came not from outright opposition, but from revealing the contradictions between Soviet rhetoric and lived reality,” explains Maria Kolesnikova, curator at the Museum of Contemporary Russian Art in Moscow. “His work forces viewers to confront how political language shapes perception.”

Though widely celebrated today, Bulatov’s art remained largely hidden from public view during most of the Soviet era. He belonged to a circle of nonconformist artists who exhibited in private apartments and workshops, away from state censorship. These “apartment exhibitions” became crucial cultural spaces where alternative artistic visions could flourish despite official repression.

Only after perestroika in the late 1980s did Bulatov’s work gain broader recognition. He moved to Paris in 1991, following the Soviet Union’s collapse, though he continued to address themes of power, language, and freedom in his later works.

In recent decades, Bulatov’s art has been exhibited at major institutions worldwide, including the Centre Pompidou in Paris, the Guggenheim Museum in New York, and Tate Modern in London. His paintings now command significant prices at international auctions, reflecting his status as one of the most important artists to emerge from the Soviet era.

Fellow artist and longtime friend Ilya Kabakov described Bulatov as “someone who never compromised his vision, even when it meant decades of official invisibility.” This principled stance established Bulatov as not merely an artist but a chronicler of how authoritarian systems attempt to colonize both public space and private consciousness.

Art historians note that Bulatov’s work has gained renewed relevance in today’s era of information manipulation and state propaganda. His visual exploration of how political language can distort reality resonates strongly in contemporary discussions about media, truth, and government power.

Bulatov leaves behind a significant artistic legacy that continues to influence younger generations of artists throughout Russia and Eastern Europe. His death marks the loss of one of the last major voices from a generation that maintained artistic integrity during one of history’s most repressive periods for creative expression.

Fact Checker

Verify the accuracy of this article using The Disinformation Commission analysis and real-time sources.

7 Comments

Sad to hear of Bulatov’s passing, but his legacy as a pioneering Soviet underground artist who challenged state propaganda through his art will surely live on. A powerful example of creative expression under authoritarian rule.

Fascinating to learn about Bulatov’s pioneering work blending Communist propaganda with natural imagery. His approach seems to have offered a unique window into the tension between state ideology and everyday reality in Soviet society.

It’s always interesting to see how artists push boundaries and find creative ways to convey social commentary, even under oppressive regimes. Bulatov’s six-decade career is an impressive legacy.

Do you know if any of Bulatov’s works are preserved in museums or private collections today? I’d be curious to see examples of his distinct visual style.

Bulatov’s use of juxtaposition to critically examine the relationship between political power and citizens’ lives sounds like an impactful artistic strategy, especially in the heavily censored environment of the Soviet era.

I wonder how his work was received and perceived by the public at the time. Did it resonate with the everyday experiences of Soviet citizens?

While the Soviet underground art scene was often marginalized, it seems Bulatov’s work managed to gain recognition and become emblematic of that movement. A pioneer whose influence likely extended beyond his home country.