Listen to the article

The sun would rise over the Rockies, and Robin Gammons would run to the front porch to grab the morning paper before school. It was a daily race—she wanted the comics while her dad sought the sports section—but the Montana Standard represented something far more meaningful in their household.

When one of the three Gammons children made honor roll, won a basketball game, or participated in History Club activities, seeing their names and achievements in the Standard’s pages validated their accomplishments. When Robin became an artist with a one-woman show at a downtown gallery, the front-page article found a permanent home on the family refrigerator, where it remains five years later, yellowed but treasured.

Two years ago, the Montana Standard reduced its print circulation to just three days a week, joining approximately 1,200 U.S. newspapers that have scaled back printing operations over the past two decades. The situation is even more dire for others—about 3,500 papers have completely shuttered during that same period, with closures continuing at an average rate of two per week this year.

This gradual disappearance represents more than just changing news consumption habits. It marks the fading of newspapers as physical objects that served multiple purposes in American households beyond merely delivering information.

“You can pass it on. You can keep it. And then, of course, there’s all the fun things,” explains Diane DeBlois, co-founder of the Ephemera Society of America, an organization of scholars and collectors focused on what they call “precious primary source information.”

“Newspapers wrapped fish. They washed windows. They appeared in outhouses,” DeBlois notes. “And—free toilet paper.”

The media industry’s downward trajectory has undeniably altered American democracy over the past two decades, with opinions divided on whether these changes have been beneficial. What’s unquestionable is how the diminishing presence of printed newspapers—once essential tools for staying informed before being repurposed for countless household uses—has subtly but significantly changed daily life.

For newspaper publishers, printing costs have become prohibitive in an industry struggling to adapt to an increasingly digital society. For ordinary Americans, the physical newspaper joins pay phones, cassette tapes, answering machines, and bank checks as objects whose disappearance marks time’s passage.

“Very hard to see it while it’s happening, much easier to see things like that in even modest retrospect,” observes Marilyn Nissenson, co-author of “Going Going Gone: Vanishing Americana.”

Nick Mathews, whose parents both worked at the Pekin (Illinois) Daily Times before he became sports editor of the Houston Chronicle and later an assistant professor at the University of Missouri’s School of Journalism, reflects on newspapers’ cultural significance beyond news delivery.

“I have fond memories of my parents using newspapers to wrap presents,” Mathews says. “In my family, you always knew that the gift was from my parents because of what it was wrapped in.”

In Houston, Mathews recalls how the Chronicle reliably sold out when local sports teams won championships, as fans sought physical keepsakes of historic moments. Four years ago, he interviewed 19 people in Caroline County, Virginia, about the 2018 closure of the Caroline Progress, a weekly paper that shuttered just before its centennial anniversary.

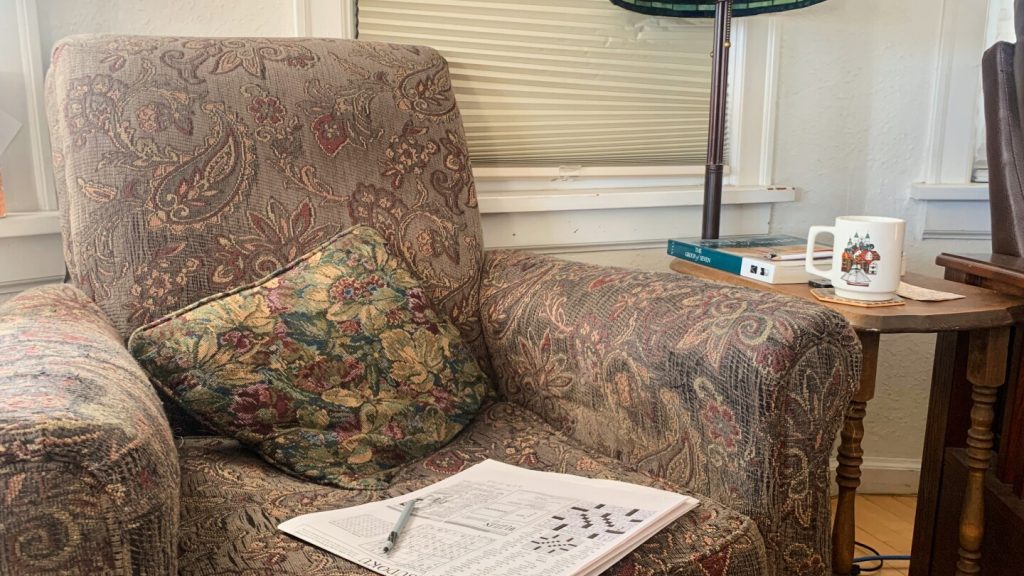

In his research, published as “Print Imprint: The Connection Between the Physical Newspaper and the Self,” residents expressed nostalgia not just for the news coverage but for the tactile experience. As one interviewee lamented, “My fingers are too clean now. I feel sad without ink smudges.”

The newspaper’s decline has practical implications beyond nostalgia. Nebraska Wildlife Rehab, which treats over 8,000 animals annually, relies heavily on donated newspapers for animal care.

“We use that newspaper for almost all of those animals,” explains Executive Director Laura Stastny. She worries that without access to free newspapers, the organization would face significant additional costs—potentially exceeding $10,000 annually, almost 1% of their budget.

The Omaha World-Herald, once owned by legendary investor Warren Buffett, exemplifies the industry’s contraction. Until 1974, it published multiple daily editions. Today, its circulation has plummeted from nearly 190,000 households in 2005 to fewer than 60,000.

In August, the Atlanta Journal-Constitution announced it would cease print publication entirely at year’s end, making Atlanta the largest U.S. metropolitan area without a printed daily newspaper.

This transition carries consequences beyond convenience. Anne Kaun, professor of media and communication studies at Södertörn University in Stockholm, notes that children in homes with printed newspapers developed news-reading habits through casual exposure—something that doesn’t naturally occur with mobile devices.

“I do think it meaningfully changes how we relate to each other, how we relate to things like the news. It is reshaping attention spans and communications,” says Sarah Wasserman, cultural critic and assistant dean at Dartmouth College.

While printed newspapers may persist in certain niches, their widespread presence in American life appears to be fading—taking with them not just news delivery but a multifaceted object that, for generations, informed, preserved memories, and served countless practical household purposes.

Fact Checker

Verify the accuracy of this article using The Disinformation Commission analysis and real-time sources.

8 Comments

As someone who grew up in a small town, I can certainly relate to the Gammons family’s fond memories of their local newspaper. The article does a great job highlighting the intangible value these publications provide beyond just the news. Their gradual disappearance is certainly concerning.

The statistics around newspaper closures are quite sobering. It’s a complex issue with no easy solutions. On one hand, I understand the economic realities driving these changes. But the loss of trusted local news sources is a real blow to civic engagement and community cohesion.

The decline of local newspapers is certainly a concerning trend. They play such an important role in documenting community life and validating the achievements of residents. I hope the Gammons family can find other ways to preserve their cherished memories from the Montana Standard.

This article highlights the broader shift in news consumption habits and the challenges facing traditional print media. While digital platforms offer convenience, there’s something irreplaceable about the physical newspaper experience. I wonder how communities will adapt as fewer local papers remain.

This is a poignant reminder of how much the newspaper industry has transformed in recent decades. The article paints a vivid picture of the special place the Montana Standard held in the Gammons household. I wonder what innovative digital solutions might emerge to fill that void.

I’m curious to learn more about the role newspapers have played in documenting the lives and achievements of ordinary people like the Gammons family. How will communities preserve that sense of shared history and identity as print media fades away?

This is a thought-provoking piece that touches on the delicate balance between economic realities and community needs. While the newspaper industry faces undeniable headwinds, the article underscores the important role these institutions play in shaping local identity and preserving shared history. I’m curious to see how this evolves.

The article raises important questions about the broader societal impacts of declining local news coverage. How will the loss of these community institutions affect things like civic engagement, government accountability, and shared cultural touchstones? It’s a complex issue worth deeper exploration.