Listen to the article

Love through the Ages: National Archives Unveils Centuries of Romance in New Exhibition

LONDON — Love is, famously, a many-splendored thing. It can encompass longing, loneliness, pain, jealousy, grief — and, sometimes, joy. As Valentine’s Day approaches, the British National Archives is exploring these multifaceted emotions in “Love Letters,” a public exhibition that spans five centuries of written expressions of love.

The exhibition, opening Saturday, brings together an extraordinary collection of documents that reveal intimate moments between both famous figures and ordinary citizens throughout British history.

“We’re trying to open up the potential of what a love letter can be,” curator Victoria Iglikowski-Broad told The Associated Press. “Expressions of love can be found in all sorts of places, and surprising places.”

The diverse collection ranges from early 20th-century classified ads seeking same-sex romance to correspondence between soldiers and their sweethearts during wartime. A medieval song about heartbreak sits alongside what Iglikowski-Broad describes as “one of our most iconic documents” — a poignant letter to Queen Elizabeth I from her longtime suitor Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester.

Written days before Dudley’s death in 1588, the letter conveys the profound intimacy between the “Virgin Queen” and the man who called himself “your poor old servant.” The missive, with “his last lettar” written on the outside, was found at Elizabeth’s bedside when she died almost 15 years later — a testament to its significance in her life.

The exhibition expands beyond romantic love to encompass family bonds. Jane Austen’s handwritten will from 1817 reveals her deep affection for her sister Cassandra, to whom she left almost everything. In a stark contrast, a 1956 letter from the father of notorious London gangster twins Reggie and Ronnie Kray pleads with a court to show leniency, claiming “all their concern in life is to do good to everybody.”

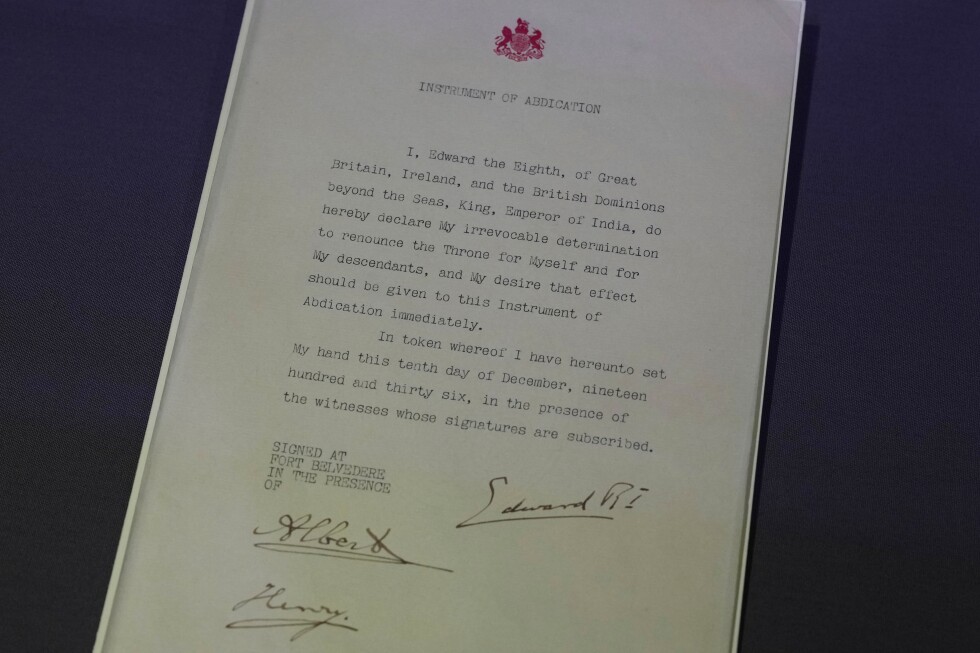

From paupers to royalty, the breadth of human experience is on display. An 1851 petition from unemployed 71-year-old weaver Daniel Rush begs authorities not to separate him and his wife by sending them to different workhouses. This humble appeal shares space with King Edward VIII’s Instrument of Abdication, through which he gave up the throne in 1936 to marry “the woman I love,” twice-divorced American Wallis Simpson.

“There is a lot of connection in these two items even though on the surface they seem very different,” Iglikowski-Broad noted. “In common they have just this human feeling of love… that the sacrifice is actually worth it for love.”

The exhibition also reveals love lost and connections that might have been. A previously undisplayed 1944 letter from British intelligence officer John Cairncross to his former girlfriend Gloria Barraclough reflects on their relationship that ended before war broke out. “Would we have broken off, I wondered, if we had known what was coming?” he wrote. What Barraclough couldn’t have known was that years later, Cairncross would be unmasked as a Soviet spy.

Some of the most compelling stories reveal love’s dangers. In one document, Lord Alfred Douglas futilely asks Queen Victoria to pardon his lover Oscar Wilde, who had been sentenced to two years in prison for gross indecency after Douglas’ father exposed their relationship.

Perhaps most haunting is a letter written in 1541 by Catherine Howard, fifth wife of King Henry VIII, to her secret lover Thomas Culpeper. Archives historian Neil Johnston describes the tone as “restrained panic. She is warning him to be very, very careful.” Catherine signed off “yours as long as life endures” — a tragically prescient phrase, as the king soon discovered the affair, and both Catherine and Culpeper were executed for treason.

A particularly rare find is a letter from Queen Henrietta Maria to King Charles I, addressing him as “my dear heart.” Unlike most royal correspondence, which remains closely guarded by the monarchy, this letter was discovered among possessions left behind by the king when he fled following a battlefield defeat during England’s civil war. Charles would ultimately lose the war and be executed in 1649.

“We don’t have very many intimate letters between monarchs like this,” Johnston explained. “This is a little gem within the disaster of the English Civil War.”

“Love Letters” runs until April 12 at the National Archives, with free admission to the public.

Fact Checker

Verify the accuracy of this article using The Disinformation Commission analysis and real-time sources.

10 Comments

A medieval song about heartbreak alongside 20th-century same-sex romance ads – what a diverse and intriguing collection. I’m impressed the National Archives is highlighting this wide range of love letters.

Absolutely, it’s great to see the Archives taking an inclusive approach and shedding light on the full spectrum of romantic experiences throughout history.

Poignant letters between soldiers and their sweethearts during wartime – that’s sure to be an emotional and powerful part of the exhibition. I wonder what insights those correspondences might offer into the human experience of love and loss.

Yes, those wartime love letters could provide a unique window into the personal toll of conflict and the enduring power of human connection, even in the darkest of times.

What an intriguing collection of love letters from British history. I’m looking forward to seeing the range of emotions and perspectives captured in these intimate writings.

I agree, exploring love through personal correspondence from different eras and social classes could provide fascinating insights.

This exhibition seems like a unique opportunity to glimpse into the hearts and minds of both famous figures and everyday people throughout Britain’s past. I wonder what sorts of stories and sentiments these letters will reveal.

Yes, I’m curious to see how the love letters of royals, soldiers, and ordinary citizens might differ or reflect common human experiences across the centuries.

The letter from Robert Dudley to Queen Elizabeth I sounds like a particularly noteworthy and iconic item in the collection. I’m curious to learn more about the backstory and context behind that piece.

Absolutely, that letter from a longtime royal suitor to the Queen must be fascinating. It could offer valuable historical perspective on power dynamics and romantic relationships in that era.