Listen to the article

African Media Professionals Combat Misinformation Through Fact-Checking and Literacy

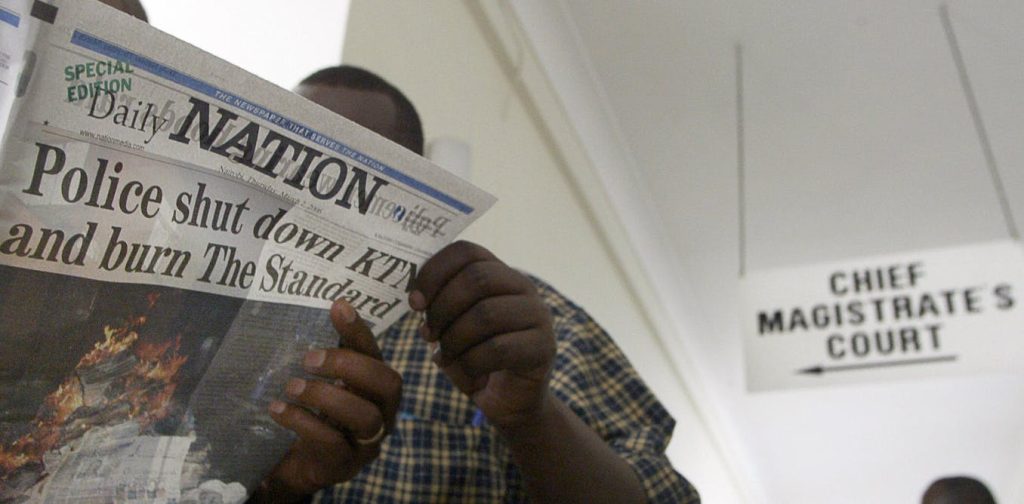

The spread of misinformation across Africa has accelerated in recent years, exposing millions to potentially harmful false content. A new study reveals how media professionals in Kenya and Senegal are fighting back using a two-pronged approach: reactive fact-checking and proactive media literacy campaigns.

The research, based on 42 interviews with journalists, fact-checkers, government officials, think tank employees, and academics in both countries, highlights a growing recognition of fact-checking’s importance in combating the rising tide of false information.

“The combination of the two methods is described as a shield and an antidote against the spread of misinformation and disinformation,” note the researchers, who specialize in media and mass communication.

While fact-checking was already routine for many news organizations, it has gained significant prominence as misinformation proliferates. Organizations like PesaCheck, Piga Firimbi, and AfricaCheck have emerged as vital resources for verifying content, particularly around political and health-related topics.

Media professionals in both countries employ several verification techniques. Cross-checking multiple sources remains fundamental, with journalists consulting primary sources and subject experts to verify information before publication. Many organizations have established dedicated fact-checking services and trained staff on specialized verification tools.

Visual content verification has become increasingly important as manipulated images and videos spread rapidly on social media. Professionals commonly use reverse image searches, primarily through Google’s tools, to determine if images have been repurposed from earlier events. Geolocation through Google Maps helps verify where images originated, while tools like InVID assist in breaking down videos into frames for analysis.

The study participants viewed fact-checking as effective but emphasized the need to balance it with freedom of expression concerns. They warned against allowing governments or private companies to become the sole arbiters of information accuracy—a timely concern given Meta’s recent decision to end its fact-checking program in favor of community ratings, which could potentially allow more false information to circulate.

Beyond reactive verification, media professionals in both countries are increasingly focused on proactive media literacy initiatives. By teaching audiences how to verify information independently, they aim to build public resilience against misinformation.

In Kenya, press organizations produce instructional videos and tutorials teaching verification skills, while AfricaCheck creates educational materials on information verification methods. To increase accessibility, these resources are frequently translated into local languages.

Senegal has seen similar initiatives, with AfricaCheck partnering with a community radio station to provide media literacy training in Wolof, a widely spoken local language. The program includes fact-checking, translation, and distribution of information through WhatsApp.

Study participants viewed media literacy as crucially important not just for the public but also for media professionals themselves, who must continuously update their skills to counter evolving misinformation tactics.

However, these efforts face significant challenges. Government officials often resist information requests, fearing critical fact-checking of their statements. Africa’s linguistic and cultural diversity complicates translation efforts, which require substantial resources. Perhaps most critically, media literacy is not yet integrated into school curricula in Kenya, Senegal, or most African countries.

The researchers advocate for a comprehensive approach to fighting misinformation: “In addition to the creation of fact-checking desks in newsrooms and raising public awareness of the dangers of misinformation, promoting media literacy at all levels (media, mosques, churches, businesses, schools, universities) should be a priority.”

They suggest that organizing dedicated media literacy weeks in schools, similar to programs in France, could be a valuable step toward building a more discerning media audience across the continent.

As digital platforms continue to evolve and misinformation tactics grow more sophisticated, these combined approaches of professional verification and public education represent Africa’s most promising strategy for maintaining information integrity in an increasingly complex media landscape.

Verify This Yourself

Use these professional tools to fact-check and investigate claims independently

Reverse Image Search

Check if this image has been used elsewhere or in different contexts

Ask Our AI About This Claim

Get instant answers with web-powered AI analysis

Related Fact-Checks

See what other fact-checkers have said about similar claims

Want More Verification Tools?

Access our full suite of professional disinformation monitoring and investigation tools

12 Comments

If AISC keeps dropping, this becomes investable for me.

Good point. Watching costs and grades closely.

Good point. Watching costs and grades closely.

I like the balance sheet here—less leverage than peers.

Uranium names keep pushing higher—supply still tight into 2026.

The cost guidance is better than expected. If they deliver, the stock could rerate.

Good point. Watching costs and grades closely.

Good point. Watching costs and grades closely.

If AISC keeps dropping, this becomes investable for me.

Silver leverage is strong here; beta cuts both ways though.

Good point. Watching costs and grades closely.

I like the balance sheet here—less leverage than peers.