Listen to the article

Study Reveals How Misinformation Spread During 2020 Election

A new study from Northeastern University has uncovered distinct patterns in how misinformation circulated on Facebook during the contentious 2020 U.S. election season, finding that false information spread through social networks in ways markedly different from typical content.

The research, published in the journal Sociological Science, shows that while most Facebook content spreads through large initial sharing events—what researchers call a “big bang”—misinformation instead traveled gradually through peer-to-peer sharing among a relatively small number of users.

“We found that most content is spread via a big sharing event, it’s not like it trickles out,” explains David Lazer, university distinguished professor of political science and computer sciences at Northeastern. “For misinformation, it’s different. Misinformation—at least in 2020—spread virally.”

Lazer and his team analyzed all posts shared at least once on Facebook from summer 2020 through February 1, 2021, mapping their distribution networks. The work was conducted as part of the Facebook/Instagram 2020 election research project, providing rare insight into the platform’s information ecosystem during a critical period.

The researchers discovered that standard content typically forms a “tree” distribution pattern that is initially wide but relatively short. For example, a post from Taylor Swift’s Facebook Page might immediately reach its 80 million followers but only be reshared a few times by individual users.

“The Taylor Swift tree would be like this giant burst, and then it would sort of trickle down,” Lazer notes. “Most of that tree would show when Taylor Swift spread it, not when David Lazer spread it.”

In stark contrast, misinformation—defined as content labeled “false” by third-party fact-checkers—created different-shaped distribution trees. These patterns showed gradual expansion as individuals shared false information with friends who then shared it further, creating what Lazer describes as a “slow burn” pattern without explosive sharing moments but persistent resharing.

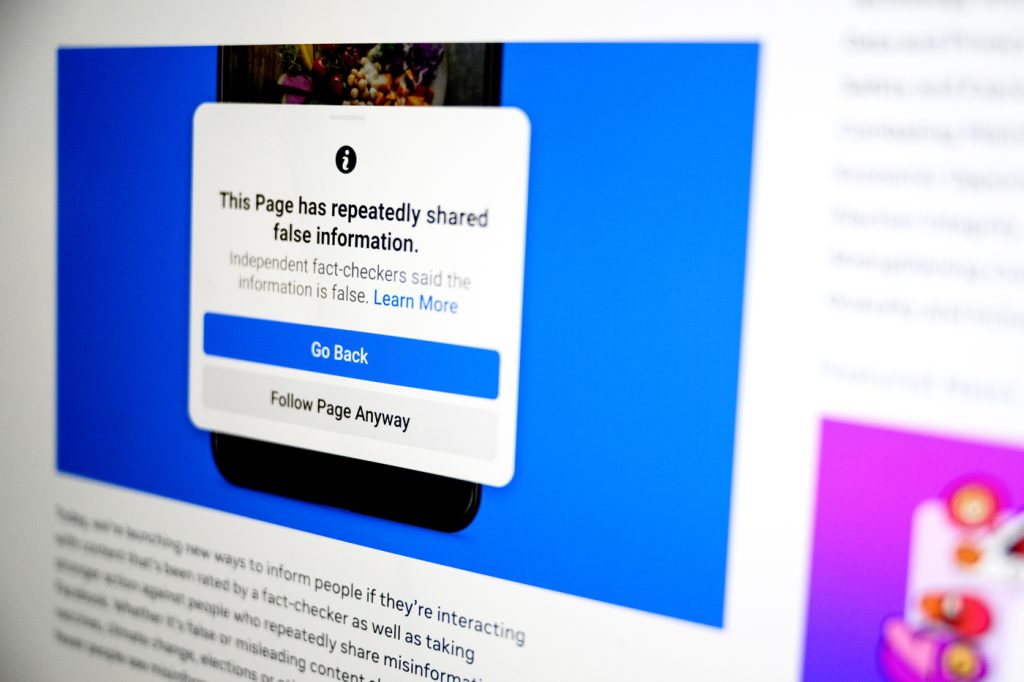

The researchers attribute these differences to Facebook’s content moderation strategies implemented during the 2020 election cycle. The platform focused enforcement efforts primarily on Pages and Groups, creating different incentives for institutional versus individual accounts.

“If the New York Times shared misinformation, then Facebook would suppress the visibility of the New York Times for a temporary period; but if I shared misinformation, nothing would happen,” Lazer explains. “So, it really created a disincentive for pages to share content that might be considered misinformation, and that just meant it just left it to users to share and reshare.”

This policy created an environment where misinformation spread primarily through individual users rather than through larger Pages or Groups. The study found that approximately just 1% of Facebook users generated the most misinformation reshares during this period.

Facebook’s enforcement measures fluctuated throughout the studied timeframe, intensifying around Election Day and after January 6, 2021, but waning during mid-to-late November and December. These “break-the-glass” emergency measures produced what Lazer called “pretty dramatic effects,” but their inconsistent application limited their overall impact.

The 2020 election season presented a perfect storm for misinformation, occurring amid a novel global pandemic, a deeply polarized electorate, declining trust in traditional media, and foreign interference. Several social media platforms implemented policies to combat false information, actions that intensified following the January 6 attack on the U.S. Capitol.

“Users sharing misinformation really couldn’t use the most effective ways of sharing content, which is sharing content via pages—so in that sense, (Facebook’s actions) probably did reduce the sharing of misinformation,” Lazer says. “But it also shows that, if you plug one hole, the water comes out faster from another hole.”

Whether Meta has subsequently addressed these alternative channels for misinformation remains unclear. Lazer notes that recent access changes and algorithm alterations mean that no equivalent study can be conducted for the 2024 election cycle, limiting researchers’ ability to determine if and how misinformation patterns have evolved since 2020.

This research provides valuable insights for platform operators, policymakers, and users seeking to understand how false information propagates through social networks during politically sensitive periods.

Fact Checker

Verify the accuracy of this article using The Disinformation Commission analysis and real-time sources.

8 Comments

This study provides fascinating insights into how misinformation spread on Facebook during the 2020 election. The gradual, viral nature of false content sharing is quite concerning compared to typical content patterns.

The distinction between how regular and false content diffuse on Facebook is quite concerning. Addressing the viral nature of misinformation is a complex but vital challenge.

It’s troubling to see how misinformation can proliferate through peer-to-peer sharing, rather than big initial events. This underscores the need for stronger moderation and education efforts around online information quality.

This study provides valuable data on the unique dynamics of misinformation spread on social media. It’s a crucial step toward developing more effective strategies to protect election integrity.

The distinctions in how regular and false content propagate on Facebook are quite eye-opening. Addressing the viral nature of misinformation is crucial for protecting democratic processes.

Interesting to see the distinction between how regular and misinformation content diffuse on Facebook. Gradual, viral spread of falsehoods is a complex issue that requires thoughtful, multifaceted solutions.

It’s troubling to see how misinformation can spread so effectively through social networks. This highlights the complex challenges platforms face in maintaining information integrity during elections.

The research findings highlight the importance of understanding the unique dynamics of misinformation spread. Social media platforms must take more proactive steps to address this challenge and protect the integrity of elections.