Listen to the article

Fighting Fake News Before It Spreads: The Prebunking Approach in North Africa

In the aftermath of Myanmar’s recent earthquake, social media platforms were flooded with dramatic footage purporting to show crumbling buildings and desperate survivors. There was just one problem: many of these videos weren’t real, but AI-generated fakes.

While possibly shared with good intentions, these fabricated clips diluted legitimate information, blurred fact and fiction, and added chaos to an already critical situation. This evolving face of misinformation—increasingly visual, emotionally charged, and difficult to verify in real-time—presents a growing global challenge.

But what if people could be prepared to resist fake news before it takes hold?

BBC Media Action has been testing this concept in North Africa, a region where such interventions are rarely studied. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the organization conducted extensive research to understand how social media users in Libya, Algeria, and Tunisia experience and react to misinformation.

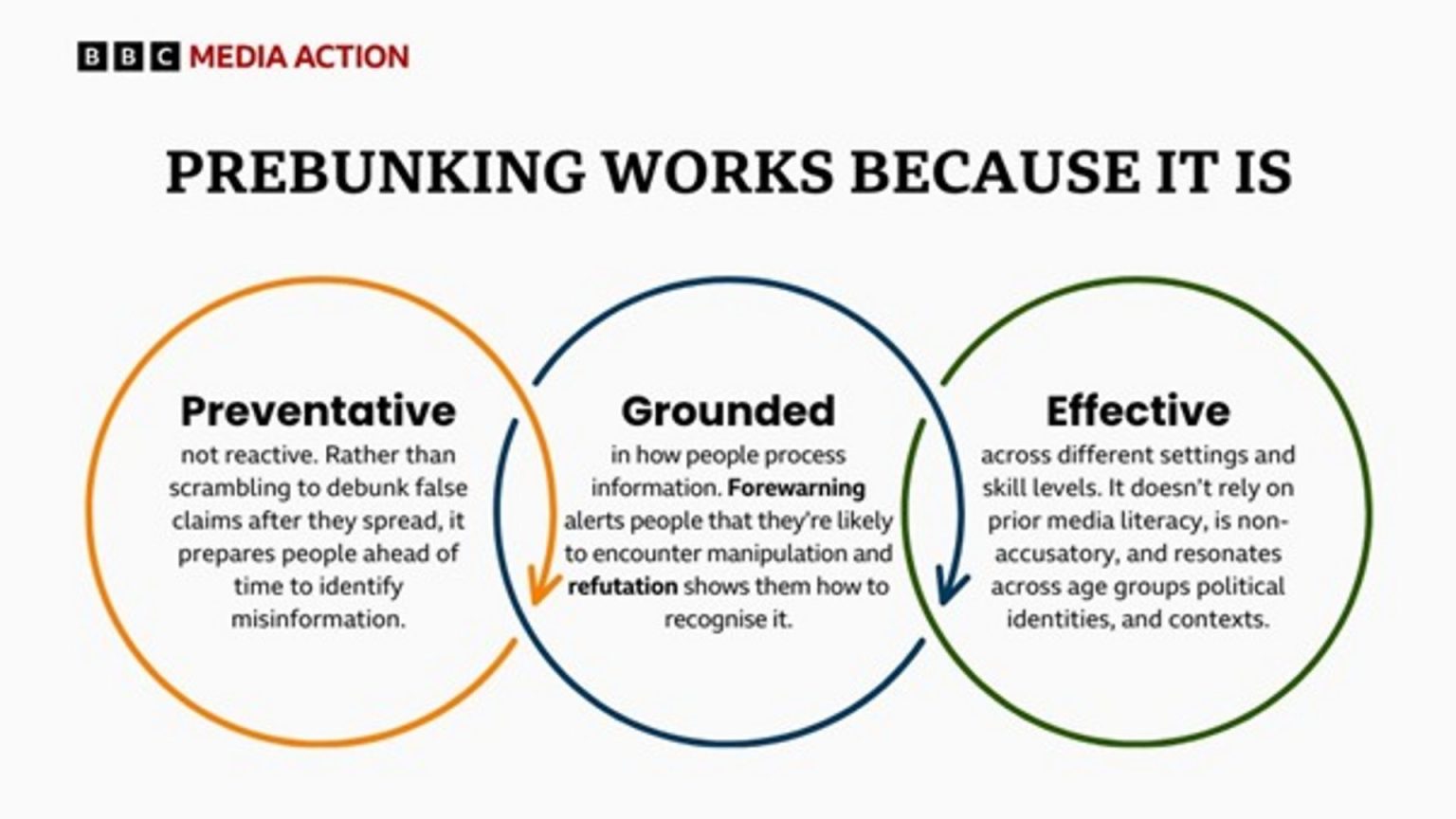

Building on these findings, they’ve implemented approaches based on “inoculation theory”—a psychological framework originally proposed in the 1960s and adapted to address misinformation by researchers at the University of Cambridge. Just as vaccines build resistance to disease by exposing the body to weakened pathogens, this approach aims to build mental resilience by exposing people to weakened versions of manipulation techniques.

“Prebunking” helps audiences recognize common manipulation tactics—emotional language, false dichotomies, personal attacks, and scapegoating—before encountering them in real situations. This approach is particularly valuable in contexts where people face high levels of misinformation but have limited tools to combat it.

Although research shows prebunking is generally effective, most studies come from high-income countries, with few attempts to apply the technique at scale in developing regions. This knowledge gap led BBC Media Action to test these methods in Tunisia and Libya.

The initial 2022 pilot in Tunisia produced mixed results. The team created two prebunking videos about emotional manipulation—one locally produced animation and one adapted from Cambridge University materials. However, neither significantly improved viewers’ ability to recognize manipulation or changed their trust and sharing behaviors.

Follow-up research revealed several challenges: emotional manipulation was so common in Tunisian media that many didn’t consider it problematic; some participants distrusted animations entirely due to their association with propaganda; and others focused on the content of test posts rather than identifying manipulative techniques.

The statistics painted a concerning picture, with 34% of Tunisian respondents believing it was more important to share information quickly than to verify its accuracy. In Libya, 35% of those surveyed reported encountering misinformation daily, with 25% taking no action when exposed.

Learning from the Tunisian experience, BBC Media Action adapted its approach for Libya. Working with the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), they conducted detailed media monitoring to identify the most prevalent manipulation techniques—emotional language and scapegoating—and produced two targeted videos.

This time, the results were encouraging. Viewers exposed to the prebunking content showed improved discernment when sharing posts containing scapegoating, becoming significantly less likely to spread such content. They also demonstrated better recognition of emotionally manipulative language, distinguishing between manipulative and non-manipulative posts.

These findings were presented at the 2025 Cambridge Disinformation Summit, contributing to broader discussions about tackling information disorder in low-trust, resource-limited contexts. The Libyan experience demonstrated that with sustained investment in local research, design, and implementation, prebunking approaches can successfully prepare audiences to recognize and slow the spread of misinformation.

BBC Media Action’s work is particularly valuable because it addresses contexts where digital connectivity is outpacing digital literacy. In these environments, the risks posed by misinformation can be more acute and damaging than in high-income countries where most research is conducted.

Looking ahead, the organization is exploring how to enhance the impact of prebunking through different formats, including long-form drama. This approach offers opportunities for repeated, narrative-driven content that can build resilience to manipulation techniques, particularly among audiences less likely to engage with traditional social media interventions.

As false narratives continue to spread faster than fact-checkers can debunk them, proactive approaches like prebunking represent a crucial shift from playing catch-up to equipping people with tools to navigate their information environment more safely and responsibly.

Fact Checker

Verify the accuracy of this article using The Disinformation Commission analysis and real-time sources.

10 Comments

Intriguing that they’re applying inoculation theory, a concept from psychology, to the challenge of online misinformation. This could be a model for other regions and contexts facing similar problems.

Yes, the potential to ‘prebunk’ misinformation before it takes hold seems like a valuable approach worth further research and implementation.

Misinformation during disasters and emergencies can have serious real-world consequences. I’m glad to see organizations like BBC Media Action testing proactive approaches to immunize people against the effects of fake news in North Africa.

Fascinating approach to combating misinformation. Preparing people to recognize and resist fake news before it spreads seems like a proactive and promising strategy. I’m curious to learn more about the effectiveness of these ‘prebunking’ interventions in North Africa.

Yes, inoculation theory is an intriguing concept. It will be interesting to see if this model can be replicated and scaled in other regions facing similar misinformation challenges.

Combating misinformation is critical, especially as AI-generated content becomes more sophisticated and difficult to detect. I’m curious to learn more about the specific ‘prebunking’ interventions used in North Africa and their measurable impact.

The rise of AI-generated fake content is a real concern, especially in crisis situations where accurate information is critical. This ‘prebunking’ initiative sounds like an innovative way to empower social media users to better discern fact from fiction.

Agreed. Educating and preparing the public to identify manipulated media and misinformation could be an effective way to build societal resilience against the spread of falsehoods online.

This is a fascinating initiative. Empowering social media users to recognize and resist the effects of fake news is an important step in the fight against misinformation. I hope the lessons learned in North Africa can be applied more broadly.

Agreed. Developing effective strategies to ‘inoculate’ the public against misinformation could have far-reaching benefits in an era of increasingly pervasive digital deception.