Listen to the article

In a revealing discussion on the transformation of Indian cinema under Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s government, experts have raised concerns about increasing political influence and censorship in the country’s film industry, which produces over 2,000 films annually across various languages.

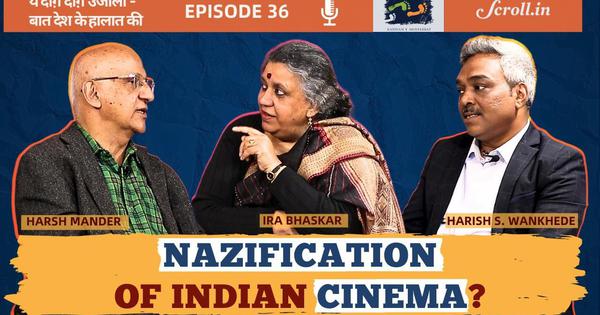

Former JNU cinema studies professor Ira Bhaskar and political science assistant professor Harish Wankhede joined social activist Harsh Mander to analyze what some critics are calling the “Nazification” of Indian cinema—a term suggesting the systematic use of film as a political tool to promote nationalist ideologies.

The panel highlighted several recent instances of film censorship that have alarmed industry observers. “Panjab 95,” which reportedly addresses sensitive historical events in Punjab, was effectively blocked from release through regulatory challenges. Similarly, “Phule,” a biopic about social reformer Jyotirao Phule, and “Homebound,” which explores contemporary migration issues, faced significant censorship hurdles before reaching audiences.

“What we’re witnessing is not random but a pattern of controlling narratives that don’t align with the government’s vision of India,” said Bhaskar during the discussion. This pattern reflects broader concerns about artistic freedom in India, which has dropped 11 places in the World Press Freedom Index since 2018.

The experts examined the ideological framework behind these decisions, noting that films receiving government support often align with particular nationalist narratives. “Dhurandhar,” mentioned specifically in the discussion, exemplifies the type of cinema currently receiving official encouragement—featuring strong nationalist themes and historical interpretations that complement the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party’s (BJP) political philosophy.

This shift in India’s cinematic landscape comes as the country’s film industry, valued at approximately $2.3 billion and expected to grow to $3.7 billion by 2024, faces increasing pressure to produce content that resonates with the government’s political agenda. The Modi administration has intensified scrutiny of film content through the Central Board of Film Certification, which critics argue has become more stringent with politically sensitive material.

The discussion also addressed the changing representation of religious and caste minorities in mainstream Indian cinema. The portrayal of Muslims and Dalits, India’s historically marginalized communities, has evolved significantly during Modi’s tenure, with experts noting a troubling trend toward either stereotypical representation or complete erasure.

“Films that once celebrated India’s diversity now often present a more homogenized version of national identity,” Wankhede observed. This shift represents a departure from Indian cinema’s post-independence tradition of promoting secular values and social equality through influential directors like Satyajit Ray, Shyam Benegal, and Ritwik Ghatak.

Despite these pressures, the panel identified a resilient counter-current of filmmakers committed to humanist and pluralistic values. Independent cinema and regional film industries, particularly in southern states like Kerala and Tamil Nadu, continue to produce works that challenge dominant narratives and explore social inequalities.

The rise of streaming platforms has also created alternative spaces for more diverse storytelling, though recent regulatory expansions have brought these platforms under greater government oversight as well. Series like “Leila” and “Tandav” on Netflix and Amazon Prime respectively have faced controversy and censorship demands in recent years.

The discussion highlights a critical moment for Indian cinema, which has historically served as both entertainment and a powerful medium for social commentary in the world’s largest democracy. As India approaches general elections in 2024, the tension between artistic expression and political pressure within its film industry continues to intensify, raising questions about the future direction of one of the world’s most prolific film cultures.

Fact Checker

Verify the accuracy of this article using The Disinformation Commission analysis and real-time sources.

33 Comments

I like the balance sheet here—less leverage than peers.

Good point. Watching costs and grades closely.

Good point. Watching costs and grades closely.

Uranium names keep pushing higher—supply still tight into 2026.

Good point. Watching costs and grades closely.

Good point. Watching costs and grades closely.

Exploration results look promising, but permitting will be the key risk.

Good point. Watching costs and grades closely.

Good point. Watching costs and grades closely.

Interesting update on India’s Propaganda Films: Examining the Driving Forces. Curious how the grades will trend next quarter.

Good point. Watching costs and grades closely.

Good point. Watching costs and grades closely.

Nice to see insider buying—usually a good signal in this space.

Good point. Watching costs and grades closely.

Good point. Watching costs and grades closely.

Nice to see insider buying—usually a good signal in this space.

Good point. Watching costs and grades closely.

Good point. Watching costs and grades closely.

If AISC keeps dropping, this becomes investable for me.

Good point. Watching costs and grades closely.

Good point. Watching costs and grades closely.

Silver leverage is strong here; beta cuts both ways though.

The cost guidance is better than expected. If they deliver, the stock could rerate.

Good point. Watching costs and grades closely.

Good point. Watching costs and grades closely.

If AISC keeps dropping, this becomes investable for me.

Good point. Watching costs and grades closely.

Exploration results look promising, but permitting will be the key risk.

If AISC keeps dropping, this becomes investable for me.

If AISC keeps dropping, this becomes investable for me.

If AISC keeps dropping, this becomes investable for me.

Good point. Watching costs and grades closely.

Good point. Watching costs and grades closely.