Listen to the article

Filmmaker’s Secret History: Péter Bokor’s Undisclosed Ties to Communist State Security

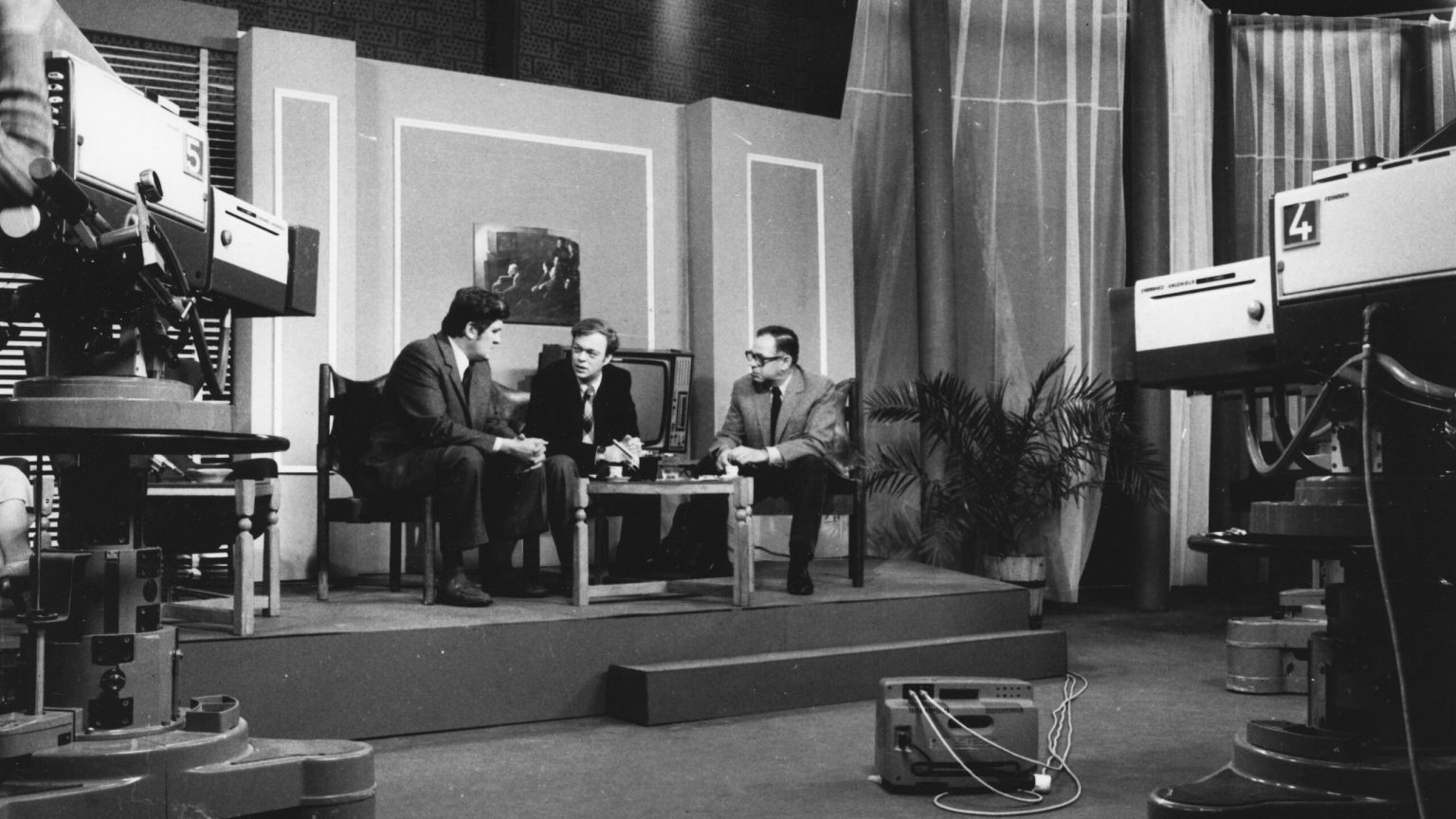

Péter Bokor, once a celebrated Hungarian film director, has left a complex legacy that extends far beyond his acclaimed historical documentary series. While remembered primarily for “Századunk” (“Our Century”), which aired on Hungarian Television from 1965 to 1989, recently uncovered documents reveal Bokor’s extensive and previously undisclosed connections to Hungary’s Communist-era state security apparatus.

Born in 1924 to a Jewish family in Kaposvár, Bokor survived the Holocaust while his brother died in forced labor at the Don River and his mother perished in Auschwitz. After liberation, he trained as a pharmacist before entering the film industry as a script editor.

While his obituaries paint him as a dedicated documentarian who created essential historical records, they conspicuously omit his work producing instructional films for the Kádár regime’s Ministry of the Interior. In 1958, Bokor wrote and directed “Boszorkánykonyha” (“The Kitchen of Witches”), an instructional film detailing Radio Free Europe’s operations, portraying it as a subversive influence. He later collaborated on a 1966 film, “Teenager Party,” which claimed to expose how Radio Free Europe manipulated Hungarian youth through programs created by “former Arrow Cross members” and “counterrevolutionaries.”

The financial records indicate these projects were considered highly important by the regime – the sound engineer alone received an exceptionally high payment of 20,000 forints for “Boszorkánykonyha.”

Evidence suggests Bokor’s relationship with state security may have begun even earlier. Documents show he was questioned in 1955 during a review of the suspicious 1949 death of György Angyal, head of MAFIRT (Hungarian Film Industry Co.). Angyal officially “committed suicide” in prison, though many suspected he was beaten to death during ÁVH (State Protection Authority) interrogation.

The most revealing documents concern Bokor’s monitoring of Karl Münch, a West German diplomat. Counter-intelligence files from 1976 show Bokor was initially targeted for recruitment as an agent but was instead classified as a “social contact” codenamed “Filmes” (Filmmaker) for Department III/I-7 of the Ministry of the Interior, which handled intelligence operations against Hungarian émigré organizations.

According to security files, Bokor attended a reception at Münch’s apartment and subsequently provided information to intelligence services, even expressing negative opinions about the diplomat who considered him a friend. A 1977 letter from Münch to Bokor found in state security files was likely obtained directly from Bokor himself.

Bokor’s historical film projects were of particular interest to state security. His 1961 documentary “Halálkanyar” (Death Bend) was made with the participation of Colonel Géza Arday, an agent codenamed “Nagy Mihály,” whose involvement was approved by intelligence services specifically to help “undermine” Hungarian émigré military organizations abroad.

Perhaps most disturbing are documents showing direct state security involvement in the production of “Századunk.” One file labeled “Materials handed over to Comrade P Bokor” contains detailed information about potential interviewees, including their addresses and notes on whether they were current or former state security agents. The document was prepared for Bokor in October 1971.

Further evidence suggests the Ministry of the Interior coordinated which agents could appear in interviews, sometimes at the highest levels of security leadership. Religious figures who might criticize the regime were blocked from participating, with the cooperation of church officials who were themselves agents.

Bokor also appears to have falsified content in the published versions of his interviews. In one documented case, he inserted fabricated statements about Communist resistance activities into the testimony of Imre Kovács, a non-Communist resistance fighter, who had explicitly stated he had “no concrete knowledge” of such matters.

This revelation stands in stark contrast to Bokor’s 1997 self-assessment, when he claimed: “I knew perfectly well that if I ever deceived someone, if I ever twisted someone’s words, then I’d be done for—no one would ever speak to me again.”

These discoveries force a reevaluation of Bokor’s legacy and the historical documentaries that continue to be cited as reliable primary sources. What was once viewed as objective historical documentation now appears compromised by state security influence and direct manipulation—revealing the complex moral compromises that characterized life under Hungary’s Communist regime.

Fact Checker

Verify the accuracy of this article using The Disinformation Commission analysis and real-time sources.

9 Comments

This article highlights the challenges faced by artists and filmmakers operating under authoritarian regimes. Bokor seems to have navigated a delicate balance, producing acclaimed historical works while also serving the state’s propaganda interests. It’s a complex legacy that deserves deeper examination.

Agreed, the tension between artistic expression and political subservience is a recurring theme in histories of cinema under communist rule. Bokor’s case illustrates the difficult choices faced by creatives in that environment.

The revelation of Bokor’s ties to the state security apparatus is troubling, as it casts doubt on the objectivity and trustworthiness of the historical records he created. This underscores the challenges of researching and interpreting the past under authoritarian regimes.

Absolutely. It’s a sobering reminder that even celebrated works of history can be shaped by the political agendas of the time. Careful analysis is required to separate fact from propaganda in such cases.

Fascinating look at Bokor’s complex relationship with the Communist state security apparatus. It seems he straddled the line between creative freedom and serving the regime’s propaganda needs. I wonder how this impacted the legacy and perception of his acclaimed documentary work.

Yes, it raises a lot of questions about the integrity and objectivity of his historical documentaries. The revelation of his state security ties casts a shadow on the authenticity of the records he created.

Bokor’s story is a cautionary tale about the corrupting influence of state power on the arts and media. While his documentaries may have held historical importance, the revelation of his ties to the security apparatus undermines their credibility. This is a troubling example of how authoritarian control can distort the historical record.

Well said. It’s a stark illustration of how even acclaimed cultural figures could be co-opted by repressive regimes to serve their own narratives. Maintaining a critical eye when examining historical sources from such contexts is essential.

The article raises important questions about the integrity of Bokor’s documentary work and the challenges of interpreting historical records produced under authoritarian rule. It’s a complex case that highlights the need for rigorous, impartial analysis when examining the past, especially when political forces may have influenced the creation of key source materials.