Listen to the article

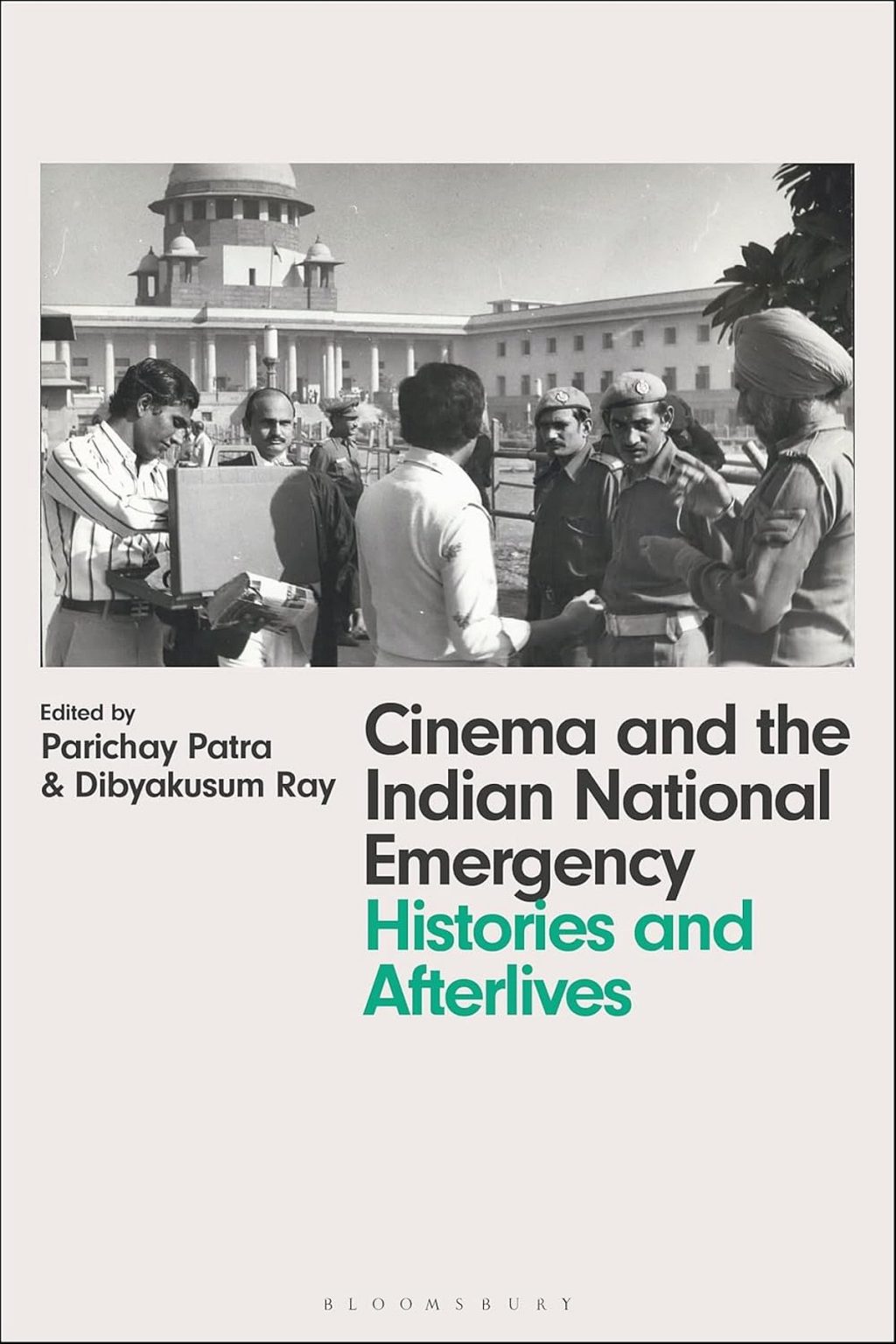

In the shadows of India’s democratic suspension, cinema found itself caught between state censorship and creative resistance during the nation’s darkest political period, according to a new scholarly analysis.

A comprehensive examination of Indian cinema during the 1975-1977 Emergency period reveals how filmmakers navigated the complex landscape of authoritarian control while still managing to express subtle criticism of the government’s heavy-handed policies.

The Emergency, declared by then-Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, suspended civil liberties, imposed press censorship, and allowed for detention without trial. This 21-month period represents one of the most controversial chapters in India’s post-independence history, fundamentally altering the relationship between the state and its cultural institutions.

Against this backdrop, the country’s vibrant film industry found itself directly in the crosshairs of government censorship. Officials recognized cinema’s potential to shape public opinion and implemented strict controls to limit dissent. Filmmakers faced unprecedented pressure to align their creative output with government narratives or risk being silenced entirely.

Film societies, which had previously served as hubs for intellectual discourse and alternative viewpoints, faced particular scrutiny. These organizations, often operating in urban centers like Mumbai, Delhi, and Kolkata, became contested spaces where the boundaries of acceptable expression were constantly negotiated and tested.

The state’s approach to documentary filmmaking during this period reveals particularly telling insights into propaganda tactics. Government-sponsored documentaries promoted official policies and achievements while carefully controlling which aspects of Indian reality were deemed suitable for public consumption. The Films Division, India’s official documentary production unit, became an important vehicle for shaping public perception during this critical period.

Parallel cinema, India’s art-house movement led by directors like Shyam Benegal, Mrinal Sen, and Adoor Gopalakrishnan, responded to these constraints in nuanced ways. These filmmakers developed sophisticated visual languages and narrative techniques that allowed them to comment on social and political realities while avoiding direct confrontation with censors. Films like Benegal’s “Ankur” and “Nishant,” while not explicitly addressing the Emergency, examined power structures and social injustice in ways that resonated with contemporary political circumstances.

Even mainstream Hindi cinema, typically viewed as escapist entertainment, participated in this complex negotiation. Commercial filmmakers incorporated coded references and allegorical narratives that allowed audiences to read between the lines. The immensely popular “angry young man” persona embodied by Amitabh Bachchan in films like “Deewar” and “Sholay” channeled public frustrations with corruption and institutional failures without directly challenging the government.

Perhaps most significantly, the analysis suggests that the Emergency’s approach to media control has cast a long shadow over Indian cultural and political life. The mechanisms of censorship, self-regulation, and state influence developed during this period established patterns that continue to shape contemporary debates about freedom of expression in India.

Today’s controversies surrounding film censorship, the targeting of dissenting voices, and the politics of representation in Indian media can be traced back to precedents set during the Emergency. The tension between artistic freedom and state authority remains a central concern in India’s cultural landscape.

The exploration of this pivotal period provides valuable context for understanding current challenges to freedom of expression in India. As the country grapples with questions about media independence and artistic liberty under different political configurations, the lessons of the Emergency era offer important historical perspective.

By examining how filmmakers, film societies, and audiences negotiated authoritarian pressure during this extraordinary period, this scholarly analysis illuminates not only a crucial chapter in India’s cultural history but also the enduring relationship between political power and creative expression in the world’s largest democracy.

Fact Checker

Verify the accuracy of this article using The Disinformation Commission analysis and real-time sources.

20 Comments

Uranium names keep pushing higher—supply still tight into 2026.

Interesting update on Cinema in Crisis: New Book Unveils Censorship, Propaganda, and Resistance in Film History. Curious how the grades will trend next quarter.

Good point. Watching costs and grades closely.

Exploration results look promising, but permitting will be the key risk.

Exploration results look promising, but permitting will be the key risk.

I like the balance sheet here—less leverage than peers.

Good point. Watching costs and grades closely.

The cost guidance is better than expected. If they deliver, the stock could rerate.

Good point. Watching costs and grades closely.

Good point. Watching costs and grades closely.

Nice to see insider buying—usually a good signal in this space.

Good point. Watching costs and grades closely.

Good point. Watching costs and grades closely.

Exploration results look promising, but permitting will be the key risk.

Interesting update on Cinema in Crisis: New Book Unveils Censorship, Propaganda, and Resistance in Film History. Curious how the grades will trend next quarter.

Good point. Watching costs and grades closely.

Good point. Watching costs and grades closely.

If AISC keeps dropping, this becomes investable for me.

I like the balance sheet here—less leverage than peers.

Good point. Watching costs and grades closely.