Listen to the article

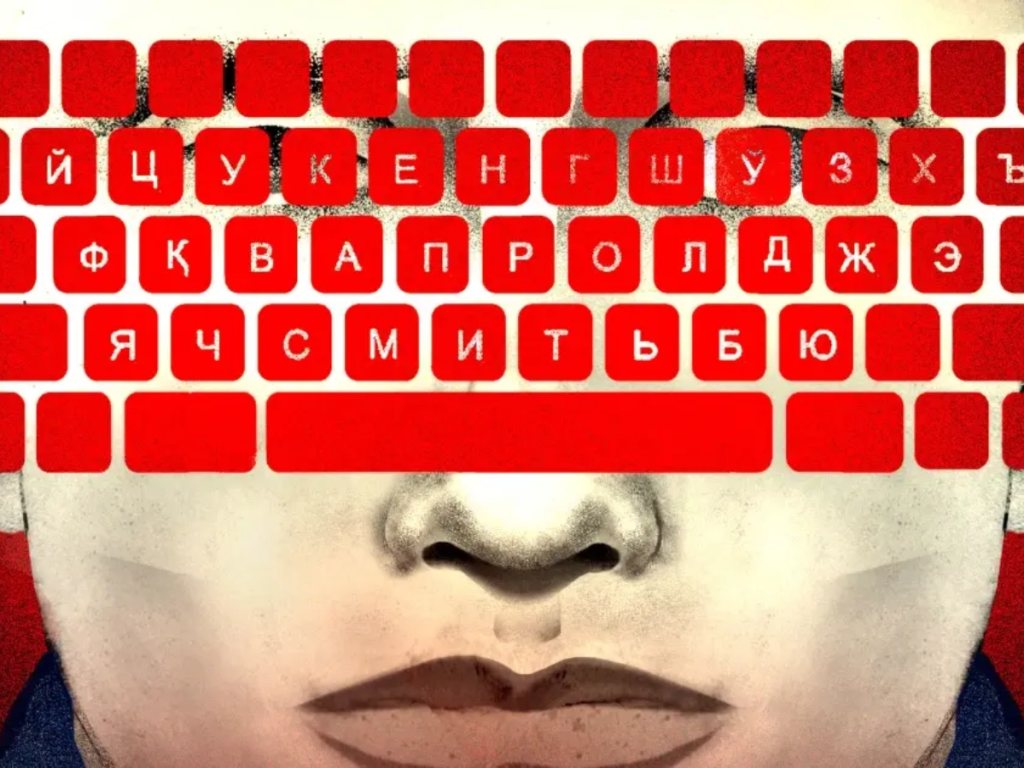

China’s Invisible Censorship: The Art of Journalistic Self-Discipline

In newsrooms across China, a familiar scenario plays out daily. A reporter files a story about a factory fire, a local protest, or a hospital scandal. Just before publication, a brief “guidance” note arrives in the newsroom chat: “Do not hype. Use only official releases. Promote stability.” Within minutes, pages are reshuffled, language is softened, and the most revealing paragraphs vanish without explanation.

The public never sees these missing pieces. In contemporary China, the most powerful form of censorship isn’t the dramatic shutdown of publications or public arrests of journalists. It’s the quiet decision to publish less, later, or not at all – a practice insiders call “self-discipline.”

This isn’t merely individual caution but a systematic approach to information control, according to Reporters Without Borders. The Communist Party’s propaganda department issues daily instructions that media organizations are expected to follow “to the letter” or face serious consequences. These instructions aren’t vague suggestions; they constitute a comprehensive framework for news coverage.

The system rests on long-established directives that categorize topics by sensitivity level and prescribe specific tones, placement requirements, and even vocabulary choices. Guidance circulated by the Central Propaganda Department mandates strict control over disasters, accidents, and “extreme events,” reserving major incident coverage for central media outlets and prohibiting “extra-territorial reporting” by regional media. The underlying logic is clear: the closer a story comes to triggering collective grief or anger, the tighter the restrictions.

On social media platforms, the mechanics of censorship are equally sophisticated but nearly invisible to users. “Ghost deletion” and filtering technologies mean a post might appear to be published but never actually circulate, or it might disappear after a brief window when few have seen it. Research on Weibo shows most deletions occur within minutes to hours, with approximately 90% of targeted content removed within 24 hours. Citizen Lab’s analysis of WeChat has documented real-time, automatic filtering of images and keywords that affects even users outside mainland China.

This environment creates powerful disincentives for journalists at the source. Why risk professional credentials for stories that platform rules will suppress before reaching an audience?

The same invisible hand governs headline writing and story framing. Editors learn to avoid not just politically incorrect conclusions but also subtle cues – adjectives implying official responsibility, verbs suggesting cover-ups, or nouns connecting local problems to national policies. According to Freedom House, news aggregators receive instructions not to “hype” sensitive subjects and employ “super algorithms” that prioritize content aligned with Xi Jinping-era messaging.

Two sectors particularly illustrate this system: entertainment and disaster reporting. In 2021, China’s broadcasting regulators moved decisively to control celebrity culture, banning “effeminate men” from television and restricting talent shows. While framed as cultural protection, these measures effectively standardized which faces and stories could dominate screens. When an industry is told to be “healthy,” it learns to proactively remove anything that might later be deemed problematic.

Disaster coverage demonstrates how omission works when lives are at stake. During the deadly Henan floods of July 2021, both foreign and Chinese media documented pressure on coverage and hostility toward independent reporting. Watchdog organizations noted leaked directives warning media against using “exaggeratedly sorrowful” tones or unauthorized casualty figures. Later official reviews found that local authorities had “deliberately” concealed deaths. For Chinese journalists, the message was clear: when tragedy cannot be fully reported, it’s safer to report less or nothing at all.

Investigative journalism has suffered most severely. Freedom House states plainly that state controls combined with economic pressure have “stifled high-quality reporting.” Investigative work is often permitted only after authorities have already opened a case, transforming journalism from its watchdog function into post-hoc explanation.

China’s media scholars call this system “guidance of public opinion” – the doctrine that news must shape sentiment to protect Party authority. According to the China Media Project, the operational meaning is straightforward: reject news “not in the interest of the Party,” prevent trends that contradict official aims, and ensure “unerring guidance” by respecting propaganda discipline.

The result is a seamless pipeline of information control. The propaganda apparatus establishes boundaries, platforms enforce invisible limits, editors internalize red lines, and reporters learn that “political incorrectness” can cost their accreditation or freedom. What the public experiences is an artificially calm information environment with no alarming spikes or messy debates – because these elements have been systematically removed upstream.

In today’s China, the most telling evidence of control isn’t what appears, but what doesn’t – the blank spaces where necessary information should have been.

Fact Checker

Verify the accuracy of this article using The Disinformation Commission analysis and real-time sources.

10 Comments

This article highlights the concerning practice of media censorship in China. While maintaining stability is important, it shouldn’t come at the expense of transparency and the public’s right to information. Journalists face tough choices in balancing official guidelines with their duty to report the full story.

The ability to shape narratives before publication is a powerful tool of control. It’s troubling to see the extent of China’s efforts to curate the information its citizens receive. A free press is essential for a healthy society – this level of censorship is deeply problematic.

You’re right, this kind of censorship erodes public trust and undermines the integrity of news reporting. It’s a concerning trend we’ve seen in many authoritarian regimes.

This article sheds light on a troubling aspect of China’s information control tactics. The ability to shape narratives before publication is a powerful tool of propaganda. A free and independent press is vital for a healthy democracy – this level of censorship is deeply concerning.

The article highlights the insidious nature of China’s information control tactics. By systematically shaping narratives before publication, the state is able to curate the information its citizens receive. This erosion of press freedoms is deeply concerning, even if it’s done under the guise of maintaining stability.

Absolutely. This practice of ‘self-discipline’ among journalists is a troubling example of how censorship can become normalized over time. It’s a disturbing window into the state’s comprehensive efforts to control the flow of information.

While stability is important, the public deserves transparency from their government and media. This article highlights how China’s censorship framework allows the state to systematically control information flows. It’s a disturbing example of how press freedoms can be gradually eroded.

This article provides a sobering look at the extent of China’s media censorship. The ability to shape narratives before publication is a powerful tool of propaganda. While stability is important, a free and independent press is vital for a healthy society – this level of information control is deeply troubling.

This article provides a chilling look into China’s comprehensive framework for controlling media narratives. The ability to shape stories before publication is a potent form of propaganda. While stability is important, a free press is essential for a healthy society – this level of censorship is deeply problematic.

The details in this article about China’s sophisticated system of information control are quite eye-opening. The practice of ‘self-discipline’ among journalists is a concerning example of how censorship can become normalized. Maintaining stability is important, but not at the expense of transparency and press freedoms.