Listen to the article

Swiss Study Reveals Troubling Link Between Misinformation and Vaccination Attitudes

A comprehensive study conducted by the Institute of Communication and Health at the Università della Svizzera italiana in Lugano has uncovered concerning patterns in how vaccination knowledge affects public health behaviors in Switzerland. The research, approved by the university’s Institutional Review Board, examined how different types of knowledge influence attitudes toward vaccination and willingness to receive or recommend vaccines.

The study surveyed 1,713 Swiss residents, creating a representative sample of the adult population across all of Switzerland’s linguistic regions. Researchers intentionally oversampled participants from French and Italian-speaking regions to allow for comparative analysis between different language groups. The data collection occurred in March 2018, predating the COVID-19 pandemic and the associated surge in vaccination misinformation.

The researchers measured three distinct types of knowledge: objective vaccination knowledge (factual understanding), subjective health literacy (self-perceived ability to process health information), and the degree to which participants were misinformed versus simply uncertain about vaccination facts.

“We found that the interaction between these knowledge types significantly impacts public health outcomes,” said a researcher involved with the study. “Most concerning is how misinformation, as opposed to simple lack of knowledge, creates resistance to positive vaccination behaviors.”

The research team used a nine-item test to measure objective knowledge, asking participants to identify whether statements about vaccines were true or false. On average, respondents answered fewer than five items correctly, revealing significant knowledge gaps among the Swiss population.

What makes this study groundbreaking is its examination of misinformation versus uncertainty. The researchers distinguished between participants who gave wrong answers (misinformed) and those who admitted uncertainty by answering “I don’t know” to knowledge questions. This distinction proved crucial in understanding vaccination attitudes.

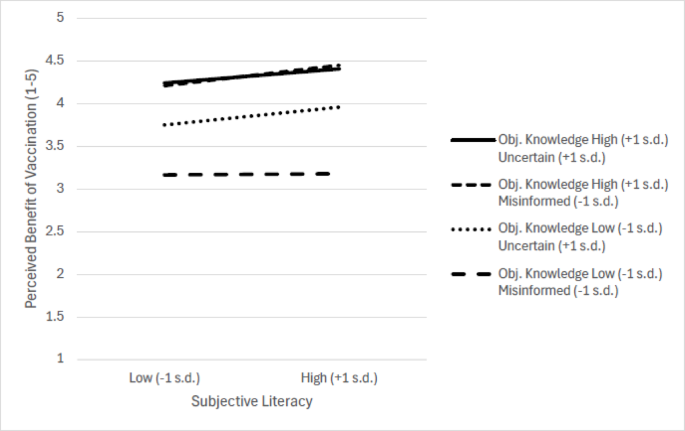

Among those with low objective knowledge, participants who were uncertain about vaccines were more receptive to health messaging than those who held incorrect beliefs. Even more revealing, participants with low objective knowledge who were misinformed showed almost no improvement in perceived vaccination benefits when their subjective literacy increased.

“This suggests that simply feeling more confident about one’s health knowledge doesn’t help if that knowledge is fundamentally incorrect,” explained one of the study’s authors. “In fact, for misinformed individuals, higher confidence may entrench their mistaken beliefs.”

The study found that objective knowledge, subjective literacy, and lower misinformation were all independently associated with more positive vaccination attitudes. However, the most important finding was how these factors interact. For individuals with low objective knowledge who were misinformed, higher subjective literacy did not increase—and sometimes even decreased—willingness to recommend vaccinations to others.

This pattern held true for actual vaccination behavior as well. The number of vaccinations received was significantly lower among misinformed individuals with high subjective literacy compared to those who acknowledged their uncertainty.

These findings have significant implications for Swiss public health strategies. The Federal Office of Public Health, which collaborated on the study, may need to reconsider traditional educational approaches that simply provide more information without addressing existing misinformation.

“Our results suggest that health campaigns should first identify and correct misinformation before attempting to build confidence in making health decisions,” noted a public health official familiar with the research.

The study also highlights the complex relationship between knowledge and behavior. While knowledge is necessary for informed health decisions, the type and quality of that knowledge matters significantly. Mistaken certainty appears more dangerous to public health than acknowledged uncertainty.

As Switzerland and other countries continue to combat vaccine hesitancy, these findings provide valuable insights for designing more effective public health communication strategies—particularly the importance of addressing misinformation directly rather than simply providing more information.

Fact Checker

Verify the accuracy of this article using The Disinformation Commission analysis and real-time sources.