Listen to the article

Preparing Students for the Misinformation Era: Why Science Education Needs Reform

In an age where information flows freely and rapidly, science faces unprecedented challenges. While scientific news is more accessible than ever, the rise of misinformation, disinformation, and pseudoscience has undermined public trust in scientific authority. The traditional gatekeepers of information—publishers and editors—have been replaced by the unrestricted space of the internet, where content can be shared widely without verification.

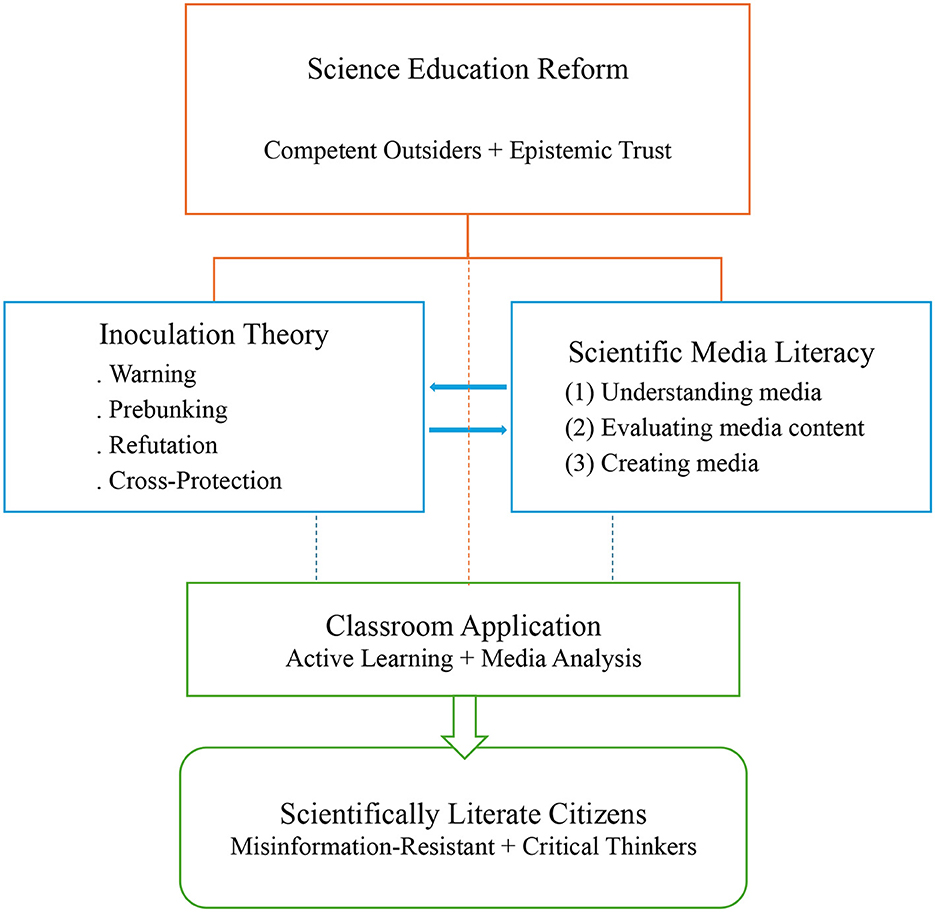

Fact-checkers struggle to keep pace with viral false claims, highlighting a critical shortcoming in our current science education model. Experts argue that science education has overlooked an essential goal: preparing students to become “competent outsiders”—individuals who may not possess deep scientific knowledge but have the evaluative skills to engage critically with scientific information.

These competent outsiders can assess scientific claims through a critical lens and judge the credibility of information presented in secondary sources, even when the underlying science exceeds their comprehension. To achieve this, educators need to reframe science as a social practice that establishes reliable consensus rather than merely a collection of facts.

“There is an urgent need for a crucial reorientation of science education and a revision of science curricula goals,” says Jonathan Osborne, who with colleagues has identified key competencies students need to develop. These include understanding our epistemic dependence on experts, recognizing deceptive tactics, and developing scientific media literacy.

After completing formal education, most people rely heavily on mass media to stay informed about critical scientific topics ranging from health to climate change. This information often presents a mix of credible science and misinformation, creating significant challenges for public understanding and decision-making.

The democratization of information has facilitated the widespread sharing of both intentional and unintentional misinformation, posing threats to science, society, and democratic processes. Studies show that misinformation often elicits negative emotions like fear and surprise, giving it an advantage in capturing human attention compared to more nuanced scientific reporting.

“As ideas compete for public attention, sensationalized and oversimplified news dominates over credible, complex scientific information,” researchers note. Journalists frequently report scientific research inaccurately, overstating progress or portraying science as a series of dramatic breakthroughs rather than a continuous process of discovery.

Inoculation theory has emerged as a leading approach for building resistance against pseudoscience and misinformation. Drawing parallels with vaccination, the theory suggests that exposing individuals to weakened forms of misinformation can help them develop “mental antibodies” against deceptive persuasion techniques.

Developed by William McGuire in the 1960s, the theory has proven remarkably adaptable to today’s digital landscape. It includes various approaches: technique-based inoculation focuses on exposing deceptive methods and logical fallacies, while fact-based inoculation corrects falsehoods with factual information.

A newer method, experiential inoculation, deliberately exposes students to misinformation before debriefing them on its misleading tactics. Research suggests that inoculation can offer broad protection without requiring issue-specific interventions, and may even provide “cross-protection” that extends beyond the specific topics addressed.

Complementing inoculation approaches, scientific media literacy refers to the ability to apply knowledge of science and media to select, understand, evaluate, and respond to various representations of science across different platforms. It encompasses understanding media context, developing evaluation skills, and creating media, though the last area is often neglected due to curriculum constraints.

Scientific media literacy offers several benefits: it connects school science to everyday life, depends on current and relevant news, increases student interest, encourages debate, and fosters lifelong learning skills. However, teachers often worry about limited instructional time, complex language in scientific articles, curriculum constraints, and the time-consuming nature of preparing appropriate materials.

Science education typically produces what experts call “marginal insiders”—graduates with knowledge of scientific concepts but only surface-level understanding of the scientific process. While content knowledge provides a necessary foundation, it’s often inadequate for making sense of the complex scientific issues encountered in everyday life.

“Public trust in science is closely tied to understanding how scientific knowledge is tested, validated, and established within the scientific community,” researchers note. Science research undergoes rigorous peer review before being accepted as reliable knowledge, a process that filters out unreliable information despite minor flaws in the system.

Experts argue that determining whether scientific claims are trustworthy and understanding how science operates as a social system should be core components of science education at all levels. This shift in focus represents a significant challenge but is essential for preparing students to navigate an increasingly complex information landscape.

Implementation faces several challenges. Teachers may resist changing familiar methods, particularly when dealing with complex or controversial topics lacking clear-cut solutions. Quality media education requires educators with solid understanding of various media genres, scientific processes, and how these elements interact.

The situation is critical but not hopeless. While misinformation presents significant challenges, a reformed science education system can help students develop the critical thinking skills needed to navigate an increasingly complex information landscape. When credible scientific research is dismissed for the wrong reasons, both science and public trust suffer—making this educational reform not just desirable but essential for our collective future.

Fact Checker

Verify the accuracy of this article using The Disinformation Commission analysis and real-time sources.

20 Comments

This is a timely and important issue. Preparing students to be ‘competent outsiders’ who can critically evaluate scientific claims is a smart move. Science education must adapt to the realities of the modern information landscape.

Preparing students to be ‘competent outsiders’ who can critically evaluate scientific claims is a smart strategy for science education. Developing these skills is essential in an era of widespread misinformation.

This is a pressing issue that science education must address. Helping students become skilled at assessing the credibility of scientific information is an important objective.

Absolutely. In an age of widespread misinformation, cultivating critical thinking skills around scientific claims is more important than ever.

In an age of rampant misinformation, the role of science education becomes even more vital. Cultivating students’ ability to assess credibility is a crucial step.

Developing students’ ability to critically evaluate scientific claims is an essential objective for science education in the modern era. Equipping them as ‘competent outsiders’ is a wise approach.

Restoring public trust in science is an uphill battle, but reforming education is a smart approach. Helping students develop the tools to think critically about scientific claims is a wise investment.

Absolutely. Giving students the evaluative skills to navigate scientific information, even without deep subject knowledge, is an important goal for science education.

This is a timely and important issue for science education. Equipping students with the ability to assess the credibility of scientific information, even without deep expertise, is a crucial goal.

I agree. Cultivating critical thinking skills around scientific claims is vital in the modern information landscape.

This is a critical issue for science education. Equipping students to navigate the sea of misinformation online is crucial. Developing critical thinking skills to evaluate claims should be a key focus.

Agreed. Empowering students to be ‘competent outsiders’ who can assess credibility is vital in the modern information landscape.

Reforming science education to focus on developing critical thinking skills is a wise move. Equipping students to navigate the complexities of the modern information landscape is crucial.

In an age of misinformation, reforming science education to focus on critical thinking skills is a prudent move. Cultivating students’ capacity to assess the credibility of scientific information is crucial.

Absolutely. Giving students the tools to navigate the complexities of the modern information landscape is a vital task for science educators.

Developing students’ capacity to critically evaluate scientific claims is a crucial challenge for education. Empowering them as ‘competent outsiders’ is a smart approach.

Reforming science education to focus on critical thinking skills is a wise strategy. Equipping students to navigate misinformation and assess credibility is an essential goal.

I agree. Developing the ability to think critically about scientific information, even without deep expertise, is a vital skill for students to acquire.

This is a timely and important challenge for science education. Empowering students to be ‘competent outsiders’ who can assess scientific claims is a smart strategy.

I agree. Helping students develop the evaluative skills to navigate scientific information, even without deep subject knowledge, is a vital goal.