Listen to the article

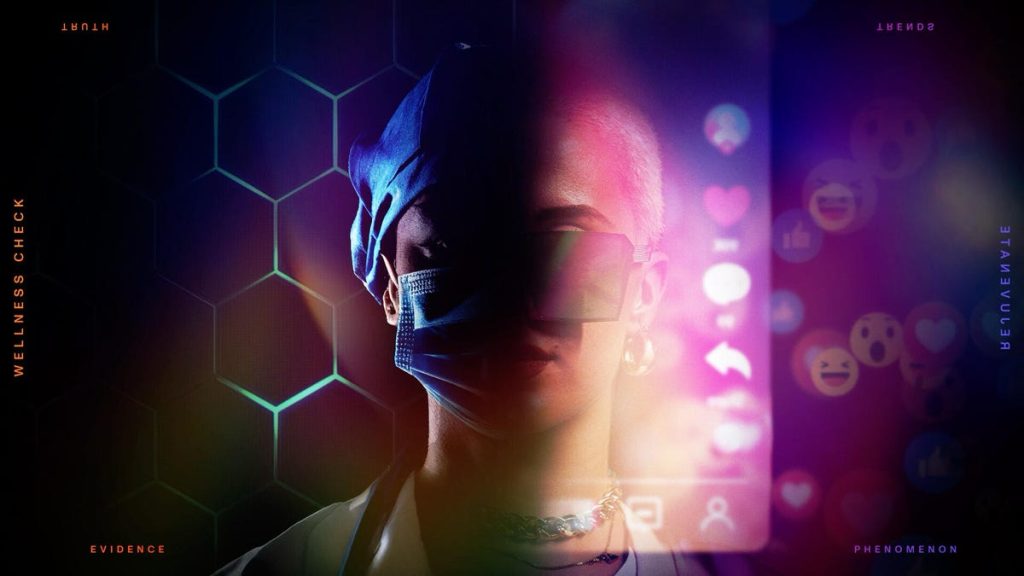

The Health Dilemma: Why We’re Turning to Social Media Instead of Doctors

I haven’t had a consistent primary care doctor since I turned 18 and moved on from the pediatrician I’d seen since birth. Though I get a yearly physical, it’s typically with a new doctor every time, depending on my location, who’s available, my insurance and which office picks up the phone—usually after several calls and endless hold music. Timely appointments are tough to come by, so if I need more immediate attention, I head to an urgent care.

When I finally do see a doctor, it’s a cold, clinical experience in a white cube of a room, more often than not with a stranger.

Compare that to wellness influencers effortlessly floating across your phone screen, making longevity, happiness, less bloating, glowing skin, and a strong immune system seem as easy as taking a supplement with your lemon water.

Answers to our pressing medical questions have never been so convenient—or alluring.

Many Americans face similar struggles accessing quality healthcare. According to a 2023 study by the National Association of Community Health Centers and the American Academy of Family Physicians, over 100 million Americans—about one-third of the U.S. population—face barriers to accessing primary care. This number has almost doubled since 2014.

Dr. Mike Varshavski, known as “Doctor Mike” to his 29 million social media followers, points to multiple factors behind healthcare’s accessibility crisis: solo practice family medicine offices closing or being bought out, fallen insurance reimbursement rates, and overwhelming administrative burdens on physicians. Family medicine remains one of the lowest-paying specialties, making fewer students inclined to pursue it.

These obstacles loom even larger for women and BIPOC communities, particularly Black women, who are more likely to experience medical gaslighting and subsequently distrust medical professionals.

Trust itself has become a significant barrier to healthcare access.

“Survey data indicates that trust in institutionalized expertise has been in decline in the U.S. since the 1950s,” says Stephanie Alice Baker, associate professor of sociology at City St George’s, University of London. “Throughout the late 20th century, a series of scandals involving the pharmaceutical and food industries has sown distrust about the financial and political motives of scientific and medical institutions.”

This erosion of trust accelerated during the COVID-19 pandemic. According to the Pew Research Center, confidence in scientists acting in the public’s best interests dropped by 14% between April 2020 and fall 2023.

Meanwhile, social media platforms offer tens of millions of videos featuring people whose lives have allegedly been transformed by wellness rituals or products. These creators promote all aspects of wellness—a multitrillion-dollar industry encompassing mental wellness, nutrition, physical activity, alternative medicine, and beauty.

But these videos don’t always prioritize viewers’ wellbeing. The spectrum ranges from legitimate medical professionals with corporate sponsorships to influencers with no medical training who profit from promoting products they claim will change your life.

The Federal Trade Commission requires that relationships between influencers and brands be disclosed with hashtags like #ad or #sponsored. Yet regardless of disclosures, these wellness videos give the impression that every aspect of your health is within your control.

“What wellness influencers do very well is make it seem like if you do X, you will be healthier,” says Jessica B. Steier, who holds a doctorate in public health and founded Unbiased Science. “It makes people feel like they have a ton of control over their health, and that’s empowering.”

It’s no wonder we get drawn in, potentially lured down rabbit holes of misinformation if influencers don’t have their facts straight—or worse, are intentionally misleading their audiences.

When Misinformation Spreads Like a Virus

As a health and wellness journalist for the past 11 years, I’ve covered countless wellness trends. What I’ve consistently learned from medical experts is that what matters most isn’t the trend of the moment, but the basic tenets of a healthy lifestyle: balanced diet, regular exercise, quality sleep, stress management, and community. But these aren’t the magic bullets that make wellness trends so marketable.

Though navigating healthcare barriers can be frustrating, having a trusted medical expert is essential so you don’t end up relying on uncredentialed influencers who promote wellness trends for personal gain—or worse, spread misinformation that puts your health at risk.

We need to think critically about what we’re encountering when we scroll.

Brian Southwell, a distinguished fellow at RTI International and adjunct professor at Duke University, defines misinformation about science as “information that asserts or implies claims that are inconsistent with the weight of accepted scientific evidence at the time.”

One infamous source of health misinformation was Belle Gibson, an Australian wellness influencer who falsely claimed to have terminal brain cancer and other illnesses, saying she healed herself naturally instead of using conventional treatments. She launched an app and cookbook, earning half a million dollars in less than two years before her deception was exposed.

Similarly, fitness influencer Brian Johnson, known as “Liver King,” promoted consuming raw animal organs and an “ancestral lifestyle” while selling supplements from his $100 million annual business. In 2022, leaked emails revealed he had been using steroids and growth hormones to achieve his muscular physique.

In more tragic cases, wellness misinformation has contributed to deaths. Paloma Shemirani died at 23 from a heart attack caused by an untreated tumor after refusing chemotherapy in favor of alternative treatments promoted by her mother, a known anti-vaccine influencer. Several anti-vaccine influencers themselves died of COVID-19 after telling followers the disease wasn’t real.

The appointment of Robert F. Kennedy Jr. as U.S. Secretary of Health and Human Services has further complicated the healthcare information landscape. RFK Jr., who has no medical background, surrounds himself with wellness influencers promoting his “Make America Healthy Again” agenda.

Why might people trust wellness influencers over doctors? The 2023 Edelman Trust Barometer found people consider someone a legitimate health expert not only when they have academic training but also when they have personal health experiences.

“People trust information from people who are similar to them or can empathize with their cultural or personal experiences,” explains Dr. Garth Graham, cardiologist and head of healthcare partnerships at YouTube and Google Health.

Among respondents who see a doctor regularly, 53% feel their physician is “slightly or not qualified” to address all their health concerns. When doctors can’t help, 65% turn to non-institutional sources like friends, family, online searches, and social media.

According to a 2023 KFF health information tracking poll, 55% of U.S. adults use social media for health information at least occasionally, with higher percentages among young adults and Black and Latinx communities.

The Tricks and Tech of the Wellness Trade

Many factors make wellness influencers persuasive beyond shared experiences. Time is a crucial element.

“People spend about 2 hours daily on social media,” says Dr. Zachary Rubin, a pediatric allergist with nearly 4 million followers. “They develop parasocial relationships where they think they know these influencers when they really don’t.”

After all, you might listen to an influencer for hours compared to just 15 minutes with your doctor.

Wellness influencers speak with authority and confidence, provide simple solutions to complex problems, and oversimplify nuanced information. According to Stephanie Baker’s book “Lifestyle Gurus,” influencers establish trust through “the three A’s: authenticity, accessibility, and autonomy.”

“The pandemic changed everything,” says Steier. “It made many of us face our own mortality and think about our health and how we’re living our lives.”

Influencers have mastered digital tools to create engaging content that captivates viewers. Andrew Pattison from the WHO notes: “To create misinformation takes minutes. To debunk it sometimes takes weeks. Creating good health content requires time, effort, knowledge and research.”

Wellness influencers also leverage platform features like TikTok Shop to promote products. Though TikTok prohibits content with medical claims or weight management products, enforcement appears inconsistent based on searches for such products.

The FDA lacks authority to approve supplements before they reach consumers, creating a regulatory gap that wellness influencers can exploit.

Medicine Meets Media

To counter misinformation, the WHO created Fides, a network of over 1,200 health professionals who use social media to spread evidence-based information. Fides provides creators with current health information and trains them to use digital platforms effectively.

“The idea is to create a movement similar to the anti-vax movement, which is small but powerful, well-coordinated, and well-funded,” explains Pattison.

In 2021, the Center for Countering Digital Hate found that just 12 anti-vaccine influencers—the “disinformation dozen”—were responsible for up to 65% of anti-vaccine content on Facebook and Twitter. This demonstrates how a few individuals can have an outsized impact on health information.

Doctor Mike Varshavski adopted social media tactics after noticing patients turning to the internet for medical advice. “What was captivating online was people selling miracle products or attacking the status quo,” he says. He now uses engaging content techniques to spread evidence-based information.

Dr. Rubin employs similar strategies on TikTok, creating hooks and catchphrases that help his medically accurate content perform better against emotionally charged misinformation.

When Followers Pay the Price—Literally

Wellness misinformation can have serious consequences beyond financial costs. A 2023 University of Sydney study analyzed about 1,000 Instagram and TikTok posts promoting five popular medical tests, including full-body MRIs and genetic cancer screenings. These posts reached approximately 200 million followers.

“Around 70% of people promoting these unproven tests had direct financial interests,” says researcher Brooke Nickel. “These tests create inequities in the healthcare system by diverting resources from people who actually need them.”

Mallory DeMille, who analyzes wellness influencers for the Conspirituality podcast, experienced the negative effects firsthand. “I was buying supplements and powders I didn’t need and restricting my diet unnecessarily,” she recalls. Since challenging wellness influencers online, she’s heard from followers who declined conventional cancer treatments based on influencer advice—sometimes with fatal consequences.

An August 2023 study found that 81% of “cancer cure” videos on TikTok featured false and misleading advice.

“The best that can happen is you lose money, time, and energy,” DeMille warns. “The real harm comes when someone forgoes evidence-based treatment because of these online parasocial relationships.”

Same Snake, Different Oil

Health misinformation isn’t new. The term “snake oil” became popular in the late 1800s after entrepreneur Clark Stanley marketed rattlesnake oil as having healing powers. Federal investigators later determined it contained no snake oil at all.

“There’s a direct connection between historic snake oil salespeople and today’s challenges,” notes Southwell. “People will always seek answers to improve their lives.”

The medical freedom movement of the 1980s promoted “healthism”—the idea that one’s worth is tied to personal health choices—which laid groundwork for today’s wellness movements. The internet has simply amplified these messages and made them more accessible.

Tech’s Role in Addressing Misinformation

Social media platforms have varying approaches to health misinformation. TikTok works with fact-checkers to identify false content, while Meta’s approach relies partly on community moderation. YouTube created a health platform featuring verified experts and labels content from accredited sources.

Dr. Rubin advocates for better verification systems to distinguish medical experts from influencers without credentials. However, experts recognize that complete censorship isn’t the answer, as scientific knowledge evolves.

“If it weren’t a problem, we’d have a tightly sanitized, censored environment,” says Southwell. “I wouldn’t want to live in that world either, so we have to manage the messiness.”

The Treatment for Medical Misinformation

While platforms have important roles to play, consumers must develop critical thinking skills about health information. Never rely on a single source—consult healthcare providers, seek multiple perspectives, verify credentials, and check for sponsorship disclosures.

Digital literacy is crucial. “Sharing posts trips the algorithm to amplify content,” warns Dr. Rubin. “Taking a moment before sharing can prevent creating echo chambers that promote unproven therapies.”

Addressing the healthcare provider shortage is also vital. The National Center for Health Workforce Analysis projects a shortage of 87,150 primary care physicians by 2037, particularly affecting rural areas.

More funding is needed for credentialed experts to communicate with the public—a time-intensive effort that often goes uncompensated. While some doctors accept sponsorships to support their educational content, they often face criticism that wellness influencers don’t experience.

“If I accept funding, I’m criticized and called a ‘shill,'” says Steier. “Meanwhile, wellness influencers without the same ethical standards make full-time livings from their content.”

Despite these challenges, the importance of effective health communication remains clear. “We have to recognize that patients are taking a journey with health information online,” says Dr. Graham. “The question is, how can we make it a better, higher-quality journey?”

What people ultimately seek online is a community that understands them. As real-world connections become harder to maintain, online influencers fill this void—sometimes with harmful consequences.

Between navigating misinformation and accessing healthcare, frustration is natural. However, we must continue thinking critically about the content we consume while pursuing truth. We’re all vulnerable to misinformation when seeking help that isn’t readily available, driven by universal desires for control over our health and lives.

Fact Checker

Verify the accuracy of this article using The Disinformation Commission analysis and real-time sources.

14 Comments

I like the balance sheet here—less leverage than peers.

Good point. Watching costs and grades closely.

Good point. Watching costs and grades closely.

Production mix shifting toward News might help margins if metals stay firm.

I like the balance sheet here—less leverage than peers.

If AISC keeps dropping, this becomes investable for me.

Good point. Watching costs and grades closely.

Uranium names keep pushing higher—supply still tight into 2026.

Good point. Watching costs and grades closely.

Production mix shifting toward News might help margins if metals stay firm.

Good point. Watching costs and grades closely.

Silver leverage is strong here; beta cuts both ways though.

Good point. Watching costs and grades closely.

Good point. Watching costs and grades closely.