Listen to the article

In a remarkable display of legal adaptability, a 19th-century law originally designed to combat fraud against the Union Army during the Civil War has found new relevance in addressing modern pandemic-related fraud schemes.

The False Claims Act, enacted in 1863, has become an increasingly important tool for prosecutors seeking to punish those who defrauded government COVID-19 relief programs. The law’s unique structure empowers ordinary citizens to initiate lawsuits against individuals or businesses they believe have cheated the federal government, offering financial incentives for those who come forward.

“See something, say something,” explained Myriam Gilles, a professor at Northwestern University’s Pritzker School of Law who specializes in the False Claims Act. “Tell us, but not only that, we’re going to give you a bounty, by giving you a cut of whatever you’re able to recover.”

This citizen-driven enforcement mechanism has proven remarkably efficient. Of the approximately 1,000 False Claims Act cases filed annually, most begin with a private individual – legally termed a “relator” – acting on behalf of the federal government. These cases carry the Latin designation “qui tam,” meaning “who sues for the king as well as himself,” reflecting their historical roots in English common law.

After a case is filed, federal prosecutors have at least two months to evaluate whether to take over the litigation, dismiss it, or allow the citizen to proceed independently. Government attorneys typically assume control of about 20% of cases each year, according to Department of Justice statistics.

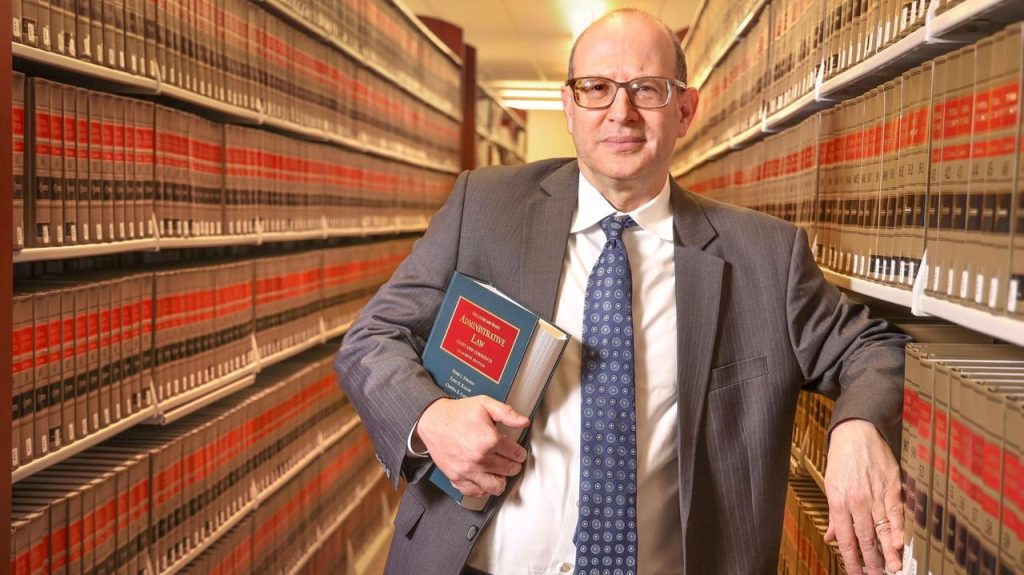

Rodger D. Citron, associate dean for research and scholarship at Touro University’s Jacob D. Fuchsberg Law Center, outlined the decision-making process: “They weigh a number of factors in deciding whether to intervene, including is the case in the public interest, the strength of the arguments and evidence, and the likelihood of recovery of the stolen funds.”

The law, sometimes called the Lincoln Act, was originally created to address rampant fraud during the Civil War. Unscrupulous contractors were notorious for selling the same horses multiple times to the Union Army, attempting to pass off crates of sawdust as muskets, and adulterating gunpowder shipments with sand – practices that endangered soldiers and undermined the war effort.

The COVID-19 pandemic created similar opportunities for fraud on an unprecedented scale. As the federal government rapidly disbursed trillions in emergency aid through programs like the Paycheck Protection Program (PPP), Economic Injury Disaster Loans, and expanded unemployment benefits, inadequate safeguards allowed widespread abuse. The Justice Department has since established specialized task forces focused on pandemic-related fraud, with the False Claims Act serving as a primary enforcement mechanism.

However, the law’s qui tam provisions have recently faced constitutional scrutiny. Supreme Court Justices Clarence Thomas, Brett Kavanaugh and Amy Coney Barrett have raised questions about whether allowing private citizens to litigate on the government’s behalf violates constitutional principles regarding executive power and separation of duties.

Legal experts suggest these challenges reflect broader ideological debates about the role of citizen enforcement in the regulatory framework. Supporters argue the False Claims Act creates an essential check on government fraud when limited enforcement resources might otherwise leave wrongdoing unaddressed. Critics counter that it potentially allows unaccountable private actors to exercise powers properly belonging to government officials.

Despite these debates, the False Claims Act continues to recover billions in fraudulently obtained government funds annually. The law’s relevance during the pandemic underscores how legislation created to address Civil War-era corruption remains remarkably effective at combating modern forms of government fraud more than 150 years later – demonstrating the adaptability of America’s legal framework to address evolving challenges to public integrity.

Fact Checker

Verify the accuracy of this article using The Disinformation Commission analysis and real-time sources.

6 Comments

The “bounty” incentive for private citizens to report fraud is an intriguing approach. Will be interesting to see if it leads to a meaningful increase in recoveries from COVID relief program cheaters, or if there are unintended consequences.

I’m skeptical that relying on private citizens to police pandemic relief fraud will be effective in the long run. Seems ripe for abuse, with potential for frivolous lawsuits and misaligned incentives. Would prefer to see stronger government oversight and auditing.

This is a fascinating legal development, using a Civil War-era law to tackle modern fraud. Curious to see if the “qui tam” whistleblower approach proves effective in rooting out COVID-19 relief scheme abuses. Could set an interesting precedent.

The False Claims Act seems like a clever way to leverage private citizens as watchdogs over government COVID relief programs. Empowering the public to act as whistleblowers and share in the recoveries could be a powerful deterrent against fraud.

From a legal perspective, it’s impressive how this 19th century law is being repurposed to address 21st century fraud. Will be fascinating to see how the courts navigate the application of the False Claims Act to pandemic-related schemes.

Interesting use of a Civil War-era law to tackle modern pandemic fraud. Gives ordinary citizens a financial incentive to report suspected misuse of COVID relief funds. Curious to see how effective this mechanism proves in rooting out fraud.