Listen to the article

Sweden’s Migration Policy Under Fire as Minister Dismisses Track Change Concerns

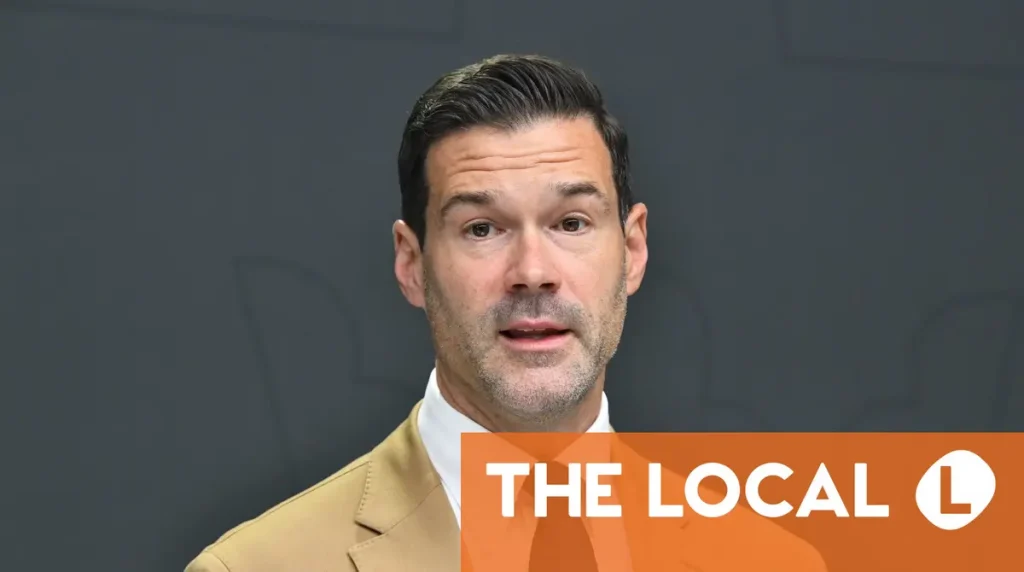

Migration Minister Johan Forssell faces mounting criticism for his stance on Sweden’s abolished “track change” law, repeatedly claiming rejected applicants can simply leave Sweden for “19 days” and reapply for work permits. This assertion, made in multiple media appearances including an interview with The Local, severely understates the reality facing thousands of foreign workers.

“All of these people can apply for a work permit, just like everyone else,” Forssell told The Local. “They have to leave the country in some cases, but the latest figures that I have seen tell me that it usually takes 19 days to get a work permit.”

The controversial policy change, implemented last April, eliminated the spårbyte (track change) provision that allowed rejected asylum seekers to switch to work permits without leaving Sweden. More critically, the change retroactively affected those who had already used the rule, even if they had applied for permit extensions before the law changed.

This has resulted in deportation orders for individuals who have spent years working, paying taxes, and integrating into Swedish society—despite having followed all legal requirements at the time.

The minister’s “19 days” claim contradicts the Migration Agency’s own statistics. According to official figures, only 75 percent of applications for “highly qualified workers” are processed within one month. For the care workers, assistant nurses, and service personnel who make up most track change cases, processing times are significantly longer.

These workers fall into the agency’s “other” category, where 75 percent of applications take up to four months (120 days) to process—more than six times longer than Forssell’s stated timeframe. The remaining quarter wait even longer.

“These are roles very often filled by immigrant workers who in many cases are overqualified,” explained a healthcare administrator at Södersjukhuset hospital in Stockholm, where Iranian couple Zahra Kazemipour and Afshad Joubeh—both now facing deportation—have worked for years. Kazemipour was described by colleagues as “one of our most skilled assistant nurses in the operating room.”

Beyond the misleading timeframe, the minister’s simplified solution ignores numerous practical challenges. Many affected individuals originally fled dangerous situations in their home countries, making return impossible. Others have no viable country to temporarily relocate to while awaiting decisions.

Financial burdens create another major obstacle. Workers must somehow fund extended stays abroad while maintaining rent and bill payments in Sweden—all without income, as they cannot work during this period. For families, children may miss months of school, disrupting education and social development.

The policy creates ripple effects across Sweden’s healthcare and service sectors, where many track changers work in already understaffed areas. Employers cannot effectively plan staffing levels or budgets with key personnel facing indefinite absences. Patients receiving specialized care from personal assistants face potential gaps in critical support services.

There are also significant questions about how these enforced absences might impact future permanent residency or citizenship applications. With Sweden planning stricter requirements for these statuses, forced departures could essentially “reset the clock” on qualifying periods.

Industry experts point out that many affected workers fill crucial roles in elder care, childcare, and healthcare—sectors already struggling with staffing shortages across Sweden. The Swedish Association of Local Authorities and Regions has previously warned that the country needs to recruit approximately 124,000 healthcare workers by 2031 to maintain current service levels.

As pressure mounts from employers, colleagues, and immigration advocates, Minister Forssell’s continued defense of the policy using the “19 days” figure has only intensified scrutiny of the government’s approach to labor migration amid Sweden’s evolving demographic and workforce challenges.

Fact Checker

Verify the accuracy of this article using The Disinformation Commission analysis and real-time sources.

4 Comments

The Minister’s comments come across as rather dismissive of the real challenges facing affected workers. A 19-day turnaround may be the goal, but the reality is likely much more disruptive for those who’ve established lives in Sweden. Hoping for a more empathetic solution.

While the government may be looking to tighten immigration rules, the retroactive impact on those who relied on the previous track change policy is concerning. I wonder if there could be a transitional period or exemptions to avoid mass deportations of long-term residents. Curious to see how this plays out.

The elimination of the track change provision seems like a harsh policy that doesn’t account for the lived reality of those affected. 19 days may be the average processing time, but that ignores the disruption and hardship faced by those who’ve built lives in Sweden. Hoping for a more compassionate approach.

Interesting development with the track changer policy in Sweden. It seems the Migration Minister is downplaying the real impact on foreign workers who now face deportation after years of contributing to the economy. I hope the government can find a more humane solution.